THE TORY government had prepared for strikes like the miners by introducing anti-union laws and testing them out at the Warrington Stockport Messenger dispute.

There is some dispute among right-wing commentators about whether the Tories wanted the strike or not. Former chancellor Lawson claimed later that the cabinet didn’t think that the miners would strike, given that it was approaching the end of winter and with all the contingency plans they had made. Nevertheless it was clear that Thatcher and her inner circle were quite prepared to face down the miners.

For the miners also, once the strike began, there was a realisation that to delay any further would only leave them in a worse position.

Thatcher, unlike some of her ministers, had a clear political perspective about the strike and its implications for the ruling class. For her this was an industrial version of the Falklands War which had to be pursued to the bitter end – no matter what the cost.

Hugo Young, in his biography of Thatcher claims that her preparations for the strike were a fairly rare example of Thatcher’s capacity for strategic planning. “She was not by heart a strategist… In the case of the miners, however, she had thought ahead. Tribal memories required it.” 1

The miners were not the only example of Thatcher’s ‘strategic planning’. It was quite clear after the Tory climbdown over Liverpool city council in July 1984 – settling to avoid a second front developing alongside the miners – that she went away and prepared revenge.2

But Thatcher and the Tories, along with the majority of the capitalist class, did not initially feel confident about testing out their new anti-union laws further against the miners. Even when they did use the anti-union laws at a later stage, their enforcement of them did not seriously determine the outcome of the strike but were rather used to sap the effective organisation of the miners’ union.

The Tories’ class law

THATCHER MADE a political calculation that if the miners could be beaten it would clear the way for further attacks on the working class. This proved to be generally correct although the long-term legacy of the strike was increasing social division and bitterness against the Tories. Initially, because the miners had fought there was a shift to the left on many social issues – even if this wasn’t immediately reflected in industrial or political struggles – something Thatcher and the Tories did not anticipate.

The unofficial strikes of check-in workers at Heathrow and the postal workers in 2003, have shown that once workers move en masse and remain united the anti-union laws can be swept aside with impunity.

Since the strike there has never been an example of the anti-union laws being used for anything other than effectively scaring the union leaders into policing their membership on behalf of the capitalist state. However, the anti-union laws are still a potential weapon that the capitalists can and will use if they think the balance of class forces is in their favour.

At the beginning of the strike the NCB did use the anti-union laws to get an injunction against flying pickets. But it consequently chose not to pursue the union for contempt of court when it was flagrantly ignored. This is something the NCB chairman of the time, Ian MacGregor, openly acknowledges in his autobiography.

Also, at different stages of the strike, other public-sector industries were instructed not to pursue injunctions against the NUM for fear of inflaming the situation to the point where other unions came out in sympathy.

Hugo Young points out how scared the Tories were of using their anti-union laws: “Only later did the full measure of the deception become clear. A senior official at the Department of Employment gave me a graphic account of the calculations. British Steel in particular, had pressed hard to go to court. But government, at the highest level, was adamant that this should not happen.

“The strategy, which had to be a political strategy, was to do nothing that might unite workers from steel, or the railways or the docks with the miners, and nothing that would undermine the commitment of around 25,000 miners, mainly in Nottinghamshire, to defy the union and carry on working.” 3

And also, according to Young, Thatcher personally intervened to give workers in public-sector industries better pay rises, in order to avoid a second front of strikes opening up. A leaked letter from a Downing Street private secretary revealed Thatcher’s wishes. It “agrees that BR [the nationalised railways] should increase its pay offer” and “accepts that the pay offer can be increased along the lines suggested.”4

Mass criminalisation

INSTEAD, THE main aspect of the law used against the miners was not the civil law contained in the anti-union legislation but a policy of mass criminalisation of the miners and their families. In every mining town and village those involved with the strike were charged en masse with criminal damage, riot, breach of the peace, assault and obstruction, to name a few.

From the early 1980s a distinct transfomation occured of Britain’s police, traditionally viewed as the paternalistic Dixon of Dock Green local bobby, into a paramilitary force. This effectively began after 1981 riots in Brixton, London and Toxteth, Liverpool. At the same time there were the first attempts to ensure the creation of a national police force in all but name through widespread national co-ordination of the actions of the different area police forces.

Again, Hugo Young points out, the “preparation of the police obliged the Home Office to [have] moved a very long way since 1981”. 5 The Police National Reporting Centre became a permanent facility after the 1981 riots in Liverpool, London and other parts of Britain.

Thatcher’s deputy Lord Whitelaw said at the height of the miners’ strike: “If we hadn’t had the Toxteth riots, I doubt if we could have dealt with Arthur Scargill.” 6

All of these processes begun and tested out then have now gone much further. They have been used overwhelmingly against striking workers and anti-capitalist/anti-establishment protesters.

In effect, the whole strike was treated as a mass public order situation by the Tory government, with the law applied in a brutal class fashion. For the first time on the streets of Britain, methods that had been tested out in Northern Ireland were used – not against alleged terrorists (although Thatcher later equated miners with terrorists) but against working people trying to defend their jobs and their communities.

In the 1970s, Militant had warned, for example during the 1977 firefighters’ strike where troops attempted to cover firefighters’ duties, that the state forces were not neutral but would be used against the working class. At the time many on the Left disagreed, believing that Britain’s police would not, even could not, behave like the police in Latin American dictatorships.

We warned that the police and other state forces were being prepared for an all-out confrontation with the working class.

Statistics could never fully convey the intimidation and brutality used by Thatcher’s boot boys in blue but they can give some indicator of the way the law was applied to the miners, their families and supporters.

During the strike over 11,000 people were arrested and over 5,000 stood trial, with over 100 being jailed.7 During the first nine months of the strike, 509 people were charged with unlawful assembly, and 137 were charged with riot – a figure higher than the total number found guilty of such charges in the previous three years; a period which included more riots in Britain (like those mentioned above) than had been experienced for decades.

The police were using the criminal law in the most blatant, shameful way to stop people getting into the coalfields and mount effective picketing. In the first 27 weeks of the strike 164,506 presumed pickets were prevented from entering Nottingham, according to the Chief Constable Charles McLachlan.8

Parts of Nottinghamshire, and Yorkshire, Scotland and Northumberland later in the dispute, became mini police states in all but name, as Thatcher’s boot boys developed an overtly political role to drive the miners back to work.

Yet, throughout the strike, no police were charged in relation to complaints brought against them. In 1991 South Yorkshire police had to pay half a million pounds in damages to 39 miners arrested on 18 June 1984 at Orgreave. The miners sued the police for assault, wrongful arrest, malicious prosecution and false imprisonment after their original trial for riot humiliatingly collapsed in 1985.

From early on in the strike up to 8,000 police a day were being mobilised to stop miners reaching picket lines. These police were drawn from 41 of Britain’s 43 police forces. Over 20,000 police in all were deployed during the 12 months of the strike. Militant reported on 27 April 1984 that the cost of policing the dispute had reached £1.5 million a day.

At that stage secondary picketing had lost its legal immunity in the first batch of anti-union laws introduced by Thatcher and the Tories, although it was not a criminal activity the police proceeded to treat it as such.

The police all the time claimed that they were acting within the realm of “operational decisions” but it was apparent from early on that the Tory government was pulling the strings. They used a national security committee set up in 1972 after the defeat Heath’s Tory government suffered at the hands of the miners. This was later renamed the civil contingencies committee.

Incredibly, the New Labour government is looking to extend their civil contingency powers after the successes of the postal workers in defying the anti-union laws and carrying out effective ‘illegal’ secondary picketing and solidarity action which forced Royal Mail managers to retreat.

Ruling class prepares for civil war

THROUGHOUT THE 1970s the ruling class was fearful of the radicalised working class moving leftwards and posing a direct threat to the continued existence of their precious capitalist system of wealth and privilege.

In 1977, Sir Robert Mark, a former head of the Metropolitan Police, fulminated about what he saw as the most serious threat to society: “I do not think that what we call ‘crimes of violence’ are anything like as severe a threat to the maintenance of tranquility in this country as the tendency to use violence to achieve political or industrial ends. As far as I am concerned that is the worst crime in the book. I think it is worse than murder.” 9

However, although the police were much better prepared than in 1972 or 1974, the way they were used by the Tories in 1984 was always a risky strategy.

The Guardian in January 1995 reported that police officers felt “betrayed by the Thatcher government and badly led by some senior officers during the 1984-85 miners’ strike, according to an official history of the Police Federation”.

The report goes on to say that “the Federation leaders and probably the great majority of chief officers would have been shocked had they discovered that there had been secret political collusion between MacGregor, Thatcher and others”. It points out that the police National Reporting Centre, which co-ordinated police action during the strike, was set up on the instructions of central government and not at senior officers’ request as was claimed at the time.

Ultimately, it was still the political factors that were decisive. The state and all its forces will prove powerless in the face of united action by key sections of workers.

The coercive apparatus of the state remains effective only while the working class remains unconscious of its own power.

The main sense in which Marxists use the term ‘state’ is to describe the institutions by which class rule is maintained. We live in a class society where the ruling class does not represent the interests of the whole population, where a minority maintains its power and privileges by exploiting the majority.

They do this partly though their control of ideas, for example, through their ownership of the mass media, their general control of education and other institutions. They try to persuade people that their system is the only and best way of organising society.

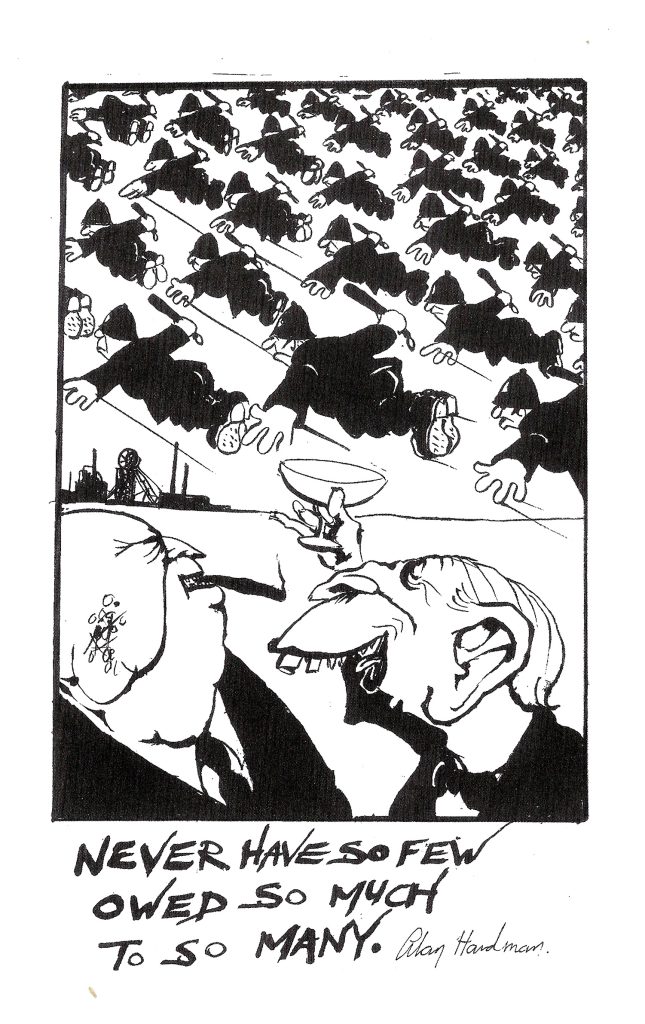

But when their ideas and system clash with the interests of working-class people, as they did in the miners’ strike, then the ruling class use the police, the courts, the law and sometimes the army to defend their profits and power.

They have specifically developed their special apparatus to ensure that their class rule continues. The core of the state, the part which it falls back on to ensure its rule when all else fails, is the repressive apparatus – the police, the army, the courts and the various intelligence agencies like Ml5. (Friedrich Engels, Karl Marx’s revolutionary co-thinker, described the state as ultimately being “a body of armed men”).

Carrying through the transition to a socialist society inevitably includes major strategic and tactical problems in defeating these agencies which exist to defend capitalist class rule.

There were a few key periods when the powers of the state, including the police and, covertly, the army, were used to try and undermine the strike; namely the first two months of attempts to picket out the Nottinghamshire and Midlands miners, secondly the flashpoint of Orgreave during May and June and then during the back- to-work movement from August onwards. During this latter period whole areas of Yorkshire, Durham and Scotland were put under siege by the police and scenes of the most appalling, indiscriminate brutality ensued. Areas like Fitzwilliam in Yorkshire and Easington in Durham were effectively sealed off to the outside world for days while the police ran amok. Militant carried some vivid eyewitness reports from these communities.10

These events showed the full brutality of the state when its rule is challenged and at the same time showed the potential power of the working class if harnessed, no matter what repressive state forces are thrown at it.

However, these occasions demonstrate that in what was no ordinary strike the ‘ordinary’ past tactics of mass picketing would also not be enough. More would have to be done in the form of solidarity action from the wider working class.

If the strategy and tactics of the miners’ leaders had developed away from a reliance on mass picketing and bureacratic deals with the trade union leaders, then no matter what state forces were thrown against the miners the strike could have reached a speedier and successful conclusion.

As we shall see later, despite the lopsided civil war that was conducted against the miners using all the forces of the state that Thatcher could reasonably use without provoking an insurrection, the miners’ resolve to win remained undaunted. This iron will caused huge cracks to open up in the capitalist class and Tory government in July and from September to October 1984, as the prospect of other unions taking strike action appeared imminent.

Events in Notts

HOWEVER, BY the latter part of May it was clear that the police action had been decisive in effectively stopping mass picketing in Notts and the prospect of solidarity action in defence of the miners’ right to carry out secondary picketing was not yet forthcoming.

At that time an editorial in Militant argued for a change of tack. Arguing that, unfortunately, “divisions were entrenched by the way the rolling strike began in March”, it said: “The fact remains that Notts have yet to be thoroughly convinced of the need for a national strike over jobs”.11 [Emphasis in original]

It argued then for an attempt to get into the Lion’s Den another way by trying official mass leafletting in Notts and approaching working miners about arranging meetings to discuss the issues, no matter how high feelings had got by that stage.

It argued for flying squads of canvassers who would take nothing for granted and it concluded: “If the Notts miners could be won over and brought out, a total British coalfield strike would get ten or a hundred times more support even than has already been shown.” (12)

Notts was a key coalfield. Clearly if it came out there would not be enough coal stocks for the Tory government to get through the winter without entering a state of emergency like Heath’s in 1974.

The very next week Militant carried an exclusive report that, even at this relatively early stage, there was a fear amongst the CEGB and government of coal stocks running dangerously low. It reported that the CEGB had shut down or curtailed the power at 55 of the country’s 57 coal powered fire stations. Only two power stations in the East Midlands – High Markham and West Burton – were operating at more than 50% capacity.

In Yorkshire, coal stock was shrinking by 140,000 tonnes per week since the start of the strike according to an inside source, a North-East Yorkshire power worker.

However, even if the stations were only getting a quarter of their supply it was possible for the stations to continue for a number of months – albeit at dangerous levels on occasions. As well as stopping the coal coming out of Nottingham, the key task was for the NUM to effectively picket out the large oil and coal burning power stations.

However, another turn of events focussed miners’ leader Arthur Scargill to concentrate on stopping coal going into steelworks.

NOTES

1 Hugo Young, One of Us, 1993 Pan Books, p367

2 Contrary to some ultra-left sects’ claims, Liverpool in itself was not the key dispute that could have delivered the solidarity to help the miners win their struggle. It would have been impossible for the council leadership to keep the Liverpool struggle at full tilt when the Tories were offering a settlement. Such a light-minded approach could have rebounded on them. For more details see Liverpool the City that Dared to Fight by Tony Mulhearn and Peter Taaffe

3 Hugo Young, One of Us, 1993 Pan Books, p370

4 ibid, p371

5 ibid, p368

6 ibid p368

7 One Militant miner, Nick Platteck, was jailed for breaking a police order by going for a pint of milk within half a mile of his pit.

8 Strike, 358 days that shook the nation, Sunday Times Insight team, p69

9 Quoted in an article by Lynn Walsh on police strategy, Militant issue 695, p5

10 Detailed eyewitness accounts of the events at Fitzwilliam were carried in Militant issue 708

11 Militant issue 700, 18 May 1984

12 ibid