“You have been fighting the legions of Hell”

Miners’ leader AJ Cook to striking miners in 1926

THE PIVOTAL showdown between the state and the miners was at Orgreave coking works, just south of Sheffield, between 23 May and18 June 1984. There were many turning points in the ebbs and flows of the battle during the 358 days of its duration, where the initiative shifted from one side to the other. The situation in Nottinghamshire at the start of the strike; the negotiations in July and September, the back-to-work movement from late August onwards, the Nacods ballot in September-October and the sequestration of the South Wales and national NUM funds were all crucial stages.

Orgreave, above others, represented a big defeat for the idea that mass picketing alone could effectively win the strike. At Orgreave all the elements of the Tory plan outlined in the Ridley Report came into play.

And there appears fairly conclusive circumstantial evidence that although Orgreave was not the ‘honey trap’ some Tories claim, it was nevertheless seen as an opportunity for the full brutality of the state to be unleashed, to serve as a warning to all workers.

At the time many miners felt uneasy about how simple it was to get to Orgreave on the crucial days of mass picketing – especially the 6th and 18th June. However, if it was a cunning plan designed to lure the miners in to a trap, then it came perilously close to unravelling.

“The chief constable of Yorkshire later conceded that that if mass picketing had continued after 18 June, the police would have had difficulty keeping the plant open.”1

The police riot

Despite the incredible odds stacked against the miners at Orgreave – particularly on 6th and 18th June – the brutality of the police sent shockwaves around the world and brought an increase of public sympathy towards the miners and their supporters.

Civil rights organisation Liberty described the unprecedented viciousness that day: “There was a riot. But it was a police riot.” 2

There are many lessons from Orgreave to be reviewed and learned from to prepare for future workers’ struggles. Inevitably, at some big battle in the future the state will look to unleash similar tactics attempting to break the morale of striking workers.

The miners were by that time better prepared than any other group of workers could have been for the battle of Orgreave. The events at the coking works did effectively represent a military-type battle and the miners were as well drilled and as disciplined as any ‘army’ in their situation could be.

But looked at overall, you draw the conclusion that the miners’ leaders – wittingly or unwittingly – chose the wrong issue and wrong battleground at Orgreave.

Confusion over steel blockade

FROM EARLY in the strike there had been much confusion about the supply of coking coal to steel plants. These plants needed a certain amount of coal for ‘care and maintenance’ so blast furnaces would not crack and be put out of commission.

Although such supplies had been maintained in 1972 and 1974, that was done in a completely solid strike where miners effectively exercised workers’ control over the movement of coal. Where this was not adhered to through agreement with other unions, the NUM provided flying pickets to stop coal being transported.

In 1972 the closure of Saltley depot in Birmingham by Arthur Scargill’s flying pickets proved a decisive moment, which led the miners to a clear victory.

But the memory of Saltley and the workers’ power it displayed was a major element in the Tories’ plans for 1984. Both sides – Arthur Scargill and Margaret Thatcher – knew that another attempt at a ‘Saltley’ could develop.3

Different factors were at play in 1984, which meant the NUM did not have the same control over the movement of coal. Not least of these was Nottinghamshire’s working and providing extra coal for steel and power plants.

Also, the use of non-union haulage drivers who would cross picket lines allowed supplies to get into steelworks. Last but not least, were the deals done by area NUM leaders, which provided more coal than was needed for just keeping the blast furnaces hot enough for continued future operation.

In May, after months of a lack of national direction on the issue, Scargill decided it was time to seal up the steel plants by increasing mass picketing. Militant did not disagree with this, as the British Steel Corporation – aided and abetted by the leadership of the ISTC, such as Bill Sirs – were clearly getting away with strike-breaking.

Many of our miners and supporters in South Wales participated in the mass pickets at Port Talbot, which were explosive and bitter on occasions. Similarly, Militant miners in Scotland participated in the huge struggles at Ravenscraig.

Hundreds of Militant members were involved at Orgreave, even though many had uneasy misgivings about what was likely to be unleashed. However, we also argued that building links with power workers and picketing of power plants would prove more effective than concentrating on the steelworks. We argued this for a number of reasons.

Orgreave – another Saltley?

MOST OF the steelworks in Britain are situated near deep-water ports for coal and ore to be unloaded. During the strike huge amounts of coal were imported into the nearby ports to service Port Talbot, Llanwern and Ravenscraig. The only site that was relatively landlocked was Scunthorpe in Lincolnshire, which was supplied with coking coal from Orgreave, 40 miles further inland.

Port Talbot, supplied much coal for Llanwern. Non-union haulage firms, as well as lorries driven by union drivers were taking coal through mass picket lines there aided by a heavy police presence.4

At Port Talbot a week of pitched battles took place outside the plant as the lorries came out. There were also other innovative tactics like a convoy of miners’ cars trying to block off the coal lorries on the M4 motorway.

But it was clear such action was not going to quickly stop the supplies getting through. Many thousands more pickets were needed and even then it was not guaranteed that it would be successful.

Scargill thought he saw his opportunity for another Saltley at Orgreave. It was not wrong to look for such an opportunity, particularly to boost the strikers in what was shaping up to be a long war. Nevertheless, the strategy at Orgreave was not adequately thought through.

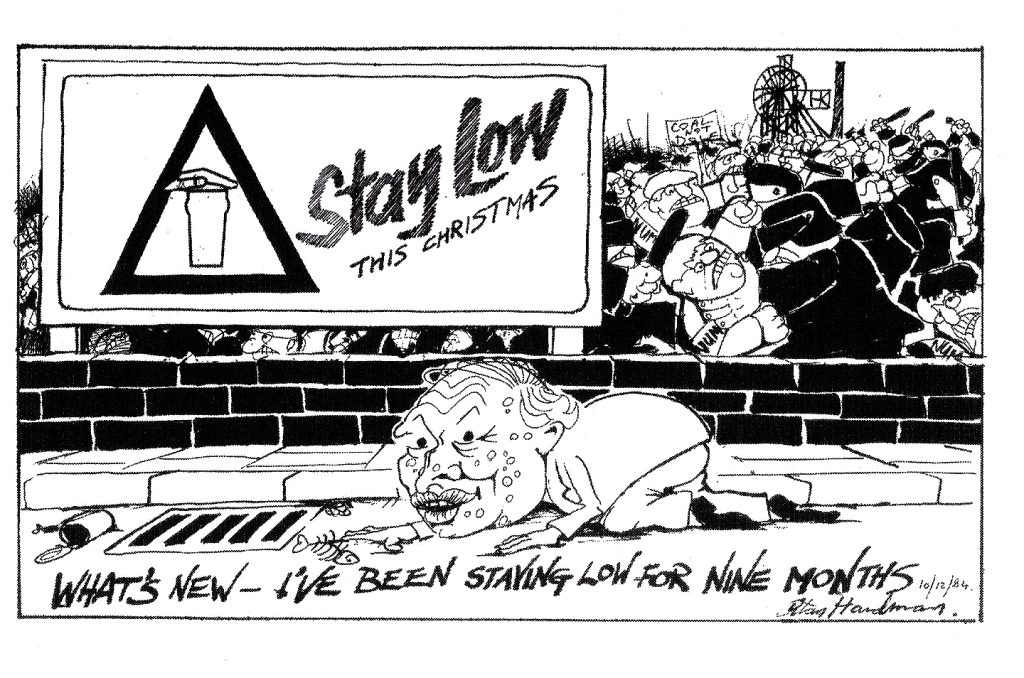

And whilst the savage beatings inflicted upon the miners and their supporters on 6 June provoked uproar and, if anything, made most miners more determined than ever not to give in, the ultimate defeat at Orgreave after 18 June caused many to question whether or not mass picketing could now achieve anything effective.

Some drew conclusions in a pessimistic one-sided way. Kim Howells was among the first to throw the baby out with the bathwater and denounce mass picketing. Responding to criticism about the increasing number of scab lorries going into Port Talbot and Llanwern steel works later on in the strike Howells said: “Challenging lines of single-minded and well-equipped policemen… had already been tried in most spectacular fashion at Orgreave… it never succeeded in stopping a single lorry nor a scab and taught us in South Wales a good deal about what to do to win friends and influence people during industrial disputes.” 5

Howells wrote a paper on co-ordinating the strike after this which was dismissed by Scargilll. From then on these two, trained in the same Communist stable, became bitter enemies.

What Howells was effectively proposing, along with some other leading lights in the South Wales NUM, was scaling down picketing – something opposed by Militant supporters in the South Wales NUM.

However, Militant miners in South Wales and other areas also had a clear alternative strategy of how to build secondary solidarity action from below, bypassing the failed official attempts at the top, which had produced nothing of any effectiveness.

The end of mass picketing?

HOWELLS WAS in a sense partly right, although we would not draw the same conclusions as he would. Orgreave was a big failure for the idea particularly beloved of groups like the SWP, that mass picketing in itself can be enough to win industrial disputes (see chapter 8).

Mass picketing can be an important part of any industrial dispute. Thatcher’s anti-union laws exist on the statute book to this day, supposedly limiting the number of pickets on a picket line to six and prohibiting secondary picketing. And, workers have increasingly shown themselves to be prepared to disregard these laws. In any current dispute the numbers picketing almost always amount to dozens, if not hundreds, and the police and government have not been able to act.

For picketing to be effective it is not just a matter of numbers; there has to be a consciousness among all workers not to cross picket lines. Also, the workers who are on strike have to have the economic muscle to shut down a workplace in a way that can force the bosses to back down.

During the postal workers’ dispute in 2003, management tried to isolate the strikers but because of the bosses’ miscalculations and the workers’ burning anger, the strike was actually spreading causing huge financial damage to Royal Mail – somewhere in the region of £50 million to £100 million.

At Orgreave in 1984 the signs for similar effective action were not as propitious. Electricity rather than Steel was the biggest customer for coal in 1984 – burning 81.8 million tonnes in 1983. Closing the generating stations or causing power cuts would have been far and away the most effective tactic. However, there were huge stocks at power stations and a mild spring and early summer meant that large-scale picketing would not have been seen by the national leadership as a realistic target – at least not until the autumn – although this was argued against by many Militant miners who were building up good links with rank-and-file power workers.

Undoubtedly, Arthur Scargill and the national NUM leadership would have been rightly wary of relying on the leaders of the power workers’ unions. These were extreme right-wingers in the pockets of Thatcher – such as Gavin Laird of the engineers, John Lyons of the power managers and Eric Hammond of the electricians, who played a notorious role as a strikebreaker in the 1986 Wapping dispute.6

Steel in contrast was not as big a prize as it was portrayed by Arthur Scargill at the time; it only consumed 4.3 million tonnes for its blast furnaces in 1983-84.

Although there had been agreement from the end of March to pinpoint supplies going into steelworks, the compromise deals reached by area leaders had undermined the prospect of it having any effect.

NUM leaders like Mick McGahey in Scotland had fought alongside members of the Scottish Tory Party and the Church of Scotland for years in a broad, cross-class alliance – a popular front campaign – claiming it was in Scotland’s ‘national’ interest rather than the interests of the Scottish working class to keep Ravenscraig near Motherwell open (see chapter 8).

Area leaders fudge the issue

BY THE end of April, the two trainloads a day McGahey had agreed to go into Ravenscraig had been stretched to such lengths by management that extra locomotives were needed to haul the trucks. Then the NUM and NUR announced they would only allow one train delivery a day.

British Steel’s response was to increase the coal being driven in by cowboy operators, offering drivers £50-£80 a day (a substantial amount at the time) and increasing the tonnage going into the plant. McGahey’s response was to try and hammer out a new two-train formula, which allowed 18,000 tonnes a week for the plant – three times the minimum needed to keep the furnaces alight.

Ravenscraig, Llanwern and Port Talbot being close to deep-water ports were not seen as good options for effective blockades. Scunthorpe though looked different, being more landlocked and dependent on domestic rather than foreign coal supplies. Its iron ore also came in from Immingham on the Humber, which was to cause further problems after the battle of Orgreave when the dockers came out on strike.

Initially, management at Scunthorpe said they were happy with the supplies of coal they were receiving and did not require any coke from Orgreave. However, seeing what other plants were getting away with and that steel production at the plant had dropped by nearly 25% they changed policy.

Then management used a problem with one of the blast furnaces to try and extract more concessions from the NUM, which were refused.

At first, pickets had some success, with relatively small numbers, in blockading Scunthorpe. But soon, cowboy drivers brought in new supplies from Flixborough on the river Trent.

Then policing was intensified at both Orgreave and Scunthorpe to allow convoys of lorries to Scunthorpe. Although the police presence was being stepped up, there were times when pickets had caught police on the hop.

Also, 300 transport union members in Scunthorpe were furious at the use of non-union labour and tried to mount their own picket line, which was viciously broken up by police. By the time of the spring bank holiday Arthur Scargill had become personally involved, believing that a mass blockade of Orgreave under his charge could become a Saltley Mark II.

In many TV, radio and press interviews of the time he built up the prospects around Orgreave implying that closing the plant would succeed because no force in the land could prevent a determined, well organised mass picket from shutting down a designated, factory, plant or workplace.

Unfortunately, given the forces stacked against the miners at Orgreave, despite their incredible bravery and heroism, Scargill’s optimism was to prove badly misplaced.

But his statements ensured that the attempt to blockade Scunthorpe through a mass picket of the Orgreave coking works 40 miles away was set to become a crucial battle to see if picketing could close a steelworks.

The battlegrounds of Orgreave

THE BATTLE for Orgreave dominated the strike for nearly four weeks from 23 May to 18 June and the coverage of it swamped many of the nightly news bulletins at the time.

One of those news bulletins became infamous for swapping round the actual sequence of events to show miners attacking police when an inquiry later revealed that it was the other way round.

On the most momentous days of battle, around 10,000 miners were confronted with 4,000-5,000 police – most of them equipped for paramilitary style conflict – along with hundreds of police ‘Cossacks’ on horses and dozens of police dogs that were unleashed by their handlers.

If any point in the strike represented graphically that there was a virtual civil war raging in the heart of Britain then it was Orgreave.

Daily news bulletins showed miners with wounds and blood streaming down their faces. One famous picture shows Lesley Boulton from a women’s support group about to be viciously truncheoned by a police outrider (this book’s front cover image). Lesley later spoke to Militant about her experience.7

The Chief Police Constable at Orgreave, Peter Wright, bluntly outlined what was at stake: “Whatever resources were needed would be provided. It was I who decided that Orgreave should stay open. I was well aware that if the pickets pulled it off at Orgreave they would move on and try it elsewhere.” 8

NCB chairman MacGregor recalls how he (and probably Thatcher as well) viewed Orgreave: “From the NCB’s point of view we had been forced by competition from foreign sources for some years to sell the coal from Cortonwood and the other pits at a price far lower than it cost us to produce. So when Arthur Scargill decided that this was going to be the battle of Saltley 1984 – it wasn’t really in the long run a critical matter to us whether he won or lost.

“If he won and Orgreave and Scunthorpe were shut, then all the NCB would have lost would have been the obligation to supply some high-cost production from a pit which we would now have an even better reason for shutting down. If he lost, then clearly, since he chose the site, the day and the weapons for the pitched battle, then it would be an enormous blow to his confidence and credibility. Either way it would keep his army out of Nottingham.” 9

Whilst there is a large dose of post-strike bravado in MacGregor’s statement it is very likely that such thoughts were being bandied around in the highest circles of the NCB and government.

On a number of occasions it looked like they were going to be left with egg on their faces. Even if strategically Orgreave wasn’t all that important for them, a victory for the miners at Orgreave would have represented a blow to the ruling class around Thatcher who wanted to win the strike, whatever it cost.

It was not long after the unprecedented violence at Orgreave, provoked by the police, that Thatcher referred to the miners as the “Enemy Within”, confirming the military and political dimension she attached to the miners’ strike. This was an insult she applied to the Militant as well.

Once started, Orgreave was a battle that neither side could afford to lose.

Thatcher and the Tories threw everything at it: state forces; propaganda; political pressure on the Labour and trade union leaders and the full force of the legal system against arrested miners.

Police ‘gladiators’ were instructed from early on by police officers with loudhailers to “take prisoners”.10 In reply the miners mobilised the biggest most determined pickets this country has ever seen.

However, despite the presence of many hundreds if not thousands of trade unionists from other unions and supporters from the support groups, ten thousand miners were not enough to resist a state onslaught of this scale. Unfortunately, despite Arthur Scargill saying correctly that the scenes were reminiscent of the police dictatorships of Latin America, he did not make a call for the wider union movement to take action to defend the miners at Orgreave.

If he had called for a 24-hour general strike of supporting unions – with or without the backing of the TUC – and on that day called for mass picket of a hundred thousand or more to show solidarity with the miners at Orgreave then matters could have taken a different turn.

Again, regretably, Scargill and the NUM leaders did not display the breadth of vision to mobilise that level of active mass support, and a huge opportunity to draw in the wider working class en masse in solidarity action went begging.

A new strategy needed

ORGREAVE REPRESENTED a big setback, which emboldened the government to be more provocative in its attacks on the miners. Until then Thatcher and the Tories had tried to maintain the pretence that this was an industrial dispute over pit closures from which they remained aloof. Of course everyone could see Thatcher pulling the strings behind the scenes.

Yet, the miners’ steadfast refusal to buckle and their willingness to defend their jobs and their union at all costs, allowed more opportunities for victory to present themselves: the dockers’ strike, the Nacods ballot and also a growing shortage of coal for the power industry in the autumn were all going to give Thatcher’s government further wobbles.

But, the defeat at Orgreave clearly put the idea of winning the strike through picketing alone on the back foot. Emboldened NCB area managers began the drive to get a small section of demoralised strikers back to work to tie up pickets in their own home areas, rather than being able to effectively picket power stations or raise funds and build wider solidarity.

From Orgreave onwards right-wing union and Labour leaders’ support for the strike – always equivocal at best – began to get more critical and echoed the propaganda of the Tories.

However, a lesson to be drawn after Orgreave was that a new strategy was needed: a strategy to build pressure on the union leaders – both Left and right – from below.

NOTES

1 The Enemy Within, Seumas Milne, Verso, London 1994, p271

2 Guardian, 20 June 1991

3 South Wales NUM research officer Kim Howells sent pickets to Saltley in March 1984 only for them to discover it had been shut in 1982

4 These drivers were members of the TGWU which was dominated in Wales by right-winger George Wright who spent more of his time during the strike witch-hunting Militant supporters than organising to assist the miners

5 Digging Deeper, Huw Benyon (editor) London 1985, p145

6 Chapter 7 on the role of the union leaders deals with this in more detail

7 Carried in Militant issue 709

8 Strike, 358 days that shook the nation, Sunday Times Insight team, Coronet 1985, p101

9 The Enemies Within, Ian MacGregor with Rodney Tyler, Fontana 1985, p207

10 Strike, 358 days that shook the nation, Sunday Times Insight team, Coronet, London 1985, p88