SOME UNION leaders knew the high stakes that a showdown with Thatcher involved. Jim Slater, leader of the National Union of Seafarers, said at the start of the strike: “We can’t afford to let the miners lose this strike. It would put us back to 1926. And it is doubtful if we would ever recover” 1 But, the Left leaders looked on almost powerless as the forces of the state were unleashed on the miners and as the strike was undermined by the right-wing union leaders. The TUC, controlled by the right wing, did not even discuss the miners’ strike until August. When, eventually it did become involved, after the TUC Congress in September, it was to conduct a lamentable exercise in procrastination and deceit.

The need to organise effective solidarity action showed, unfortunately, the incapacity of even the best union leaders to do so. Even where unions were controlled by Left leaders who may have genuinely wanted to assist the miners they seemed to lack the ideas or means to achieve it.

Most Left leaders genuinely did not want the miners to lose, regardless of how they felt towards Arthur Scargill or the other miners’ leaders. However, the Left union leaders, even the NUM as we have seen, had not prepared sufficiently – either politically or organisationally – for the inevitable showdown with Thatcher.

Certainly amongst a layer of activists from early on in the strike, there was a concern that the NUM leaders (and the Left leaders of other unions) were refighting the battles of the 1970s. In using the same tactics and strategy, rather than facing up to the different character of this struggle, particularly as the strike escalated and stretched into a marathon struggle, they showed themselves incapable of inspiring the broad mass of trade unionists who wanted to act alongside the miners.

Many of the bigger unions in 1984 were in words more to the Left and with a better degree of organisation at shop steward level than exists today, even with the recent rise of the ‘awkward squad’ (although even then a drift to the right was becoming evident).

So how, then, could they not deliver the solidarity action that was needed – particularly given the huge wave of support for the miners that developed amongst the organised working class and society generally?

Ultimately, the Left had lost touch with the rank and file and lacked the confidence to show the decisive leadership required. They did not have the strategic and tactical understanding necessary to take the strike forward at key stages. And they did not have the willingness to struggle and go to the end that the rank-and-file miners showed during the strike.

In particular, the Left union leaders had not built Broad Lefts, with links to every level of the rank and file, capable of delivering the effective action needed to win the miners’ strike, in their own unions. Also, they had not helped to build strong Left currents in the right-wing unions which could have transformed those unions during the course of the strike.

A Broad Left is a body within a union, which brings all the best Left activists together from every level of the union. When working effectively a Broad Left can co-ordinate and defeat right-wing ideas in the union and act as a transmission belt between the top and bottom of the union in a way which holds the leadership genuinely to account.

Even in the NUM, many of the Left leaders, with a few exceptions, were found wanting. Had there been an open rank-and-file based Broad Left in the NUM before the strike started, especially involving people in Nottingham, then many aspects of the strike would not have developed in such a complicated fashion.

Instead, the NUM Broad Left was a semi-secret body of 50 senior full-time officials, even though the Left had a 13-11 majority on the NEC from Scargill’s election as president. Only later in the strike were there attempts to bring in new blood from the rank and file and make it more open, but it was too little too late.

Also, if the miners and other Left unions had assisted by example and practical guidance in building Broad Lefts in other unions, especially the power workers, these could have challenged the corrupt right-wing leadership in those unions. That would have made solidarity action from below – bypassing the obstruction of the right-wing national union leaders – much easier to build.

The Left had control of the NUM at a national level and in most of the key areas. The majority of the rank-and-file miners, as was shown during the strike, were well to the Left in terms of industrial militancy and political consciousness.

But the majority of miners were not involved in the decision making about how the strike would develop.

The Left leadership in the areas were a hybrid mixture of long-standing Communist Party and Labour Lefts who had long controlled their areas throughout periods of right-wing dominance in the NUM and a newer Left who had come to prominence in the 1970s’ strikes.

They had become accustomed to a way of working with the nationalised coal board management which involved arriving at ‘consensus’ decisions, often decided by only a small layer of union officials. That method of working was something they replicated in their running of the NUM and the strike.

The Left had developed as a small tightly organised, even secretive Broad Left inside the NUM in the days of right-wing domination. No Left leaders had attempted to build a genuine mass Broad Left that involved the rank and file of the union. Often, left-wing officials at national and local level were excluded from the Broad Left.

Under pressure

DURING THE strike a new generation of Left leaders began to come forward in the NUM and other unions. If the strike had been successful, along with the successful struggle in 1984 of the Militant-led Liverpool city council, this would have undoubtedly consolidated a huge shift to the Left in most unions and probably inside the Labour Party also.

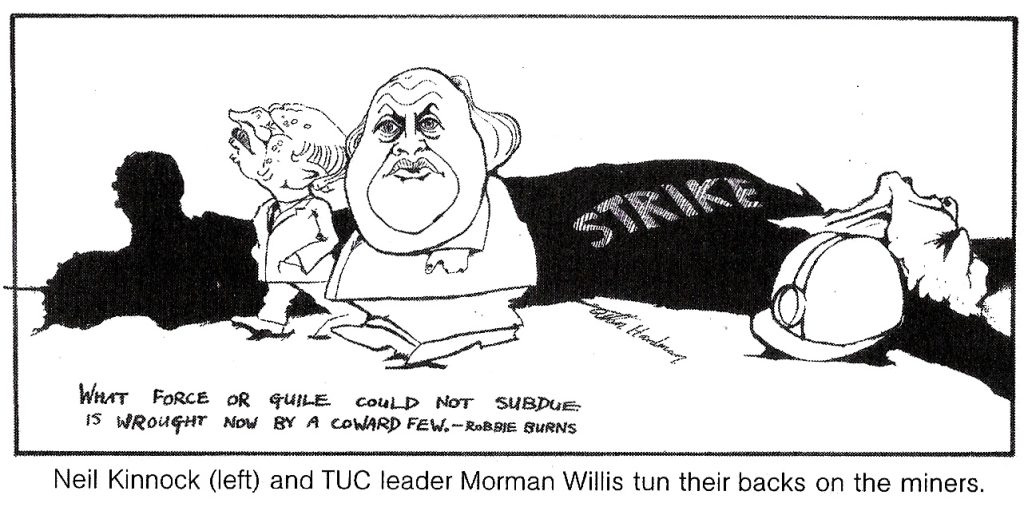

This was something some union leaders and especially Labour leader Neil Kinnock did not want. The idea that militancy could bring results was something that would put them under enormous pressure and, as noted earlier, the majority of the leadership of the labour movement were moving rightwards after Labour’s 1983 election defeat.

In contrast, Arthur Scargill was different to many of the NUM Left leadership and the other Left leaders in the unions. He undoubtedly had no intention of selling his membership or working-class people short.

During the strike and since Scargill has shown an unyielding defiance of the capitalist system and has not – unlike many of the strike’s leading figures – renounced his past or the strike.

But, Scargill also often operated in isolation, lacking confidence in the people around him and inevitably making avoidable mistakes.

This partly stemmed from his initial membership of the Young Communist League and association with Stalinist CP industrial organisers, which encouraged a top-down approach to organising. And although he was very effective in inspiring the rank and file of the NUM, the way in which the NUM Left was organised did not bring in the best of the new generation at key stages in the strike when the old Left began to act as a brake on the struggle.

Also, on certain key issues, he placed too great an emphasis on one-off actions like the mass pickets at Orgreave. And his advocacy of the NUM’s political and financial links to Stalinist regimes like the Soviet Union and one-party states caused certain problems later on in the strike, when the press conducted a witch-hunt relating to the NUM’s finances after Roger Windsor visited Libya (without Scargill’s knowledge).

But, the right wing’s claim that the strike was all about Scargill’s ‘character’ and that his belligerent stance was solely responsible for calling out over 150,000 miners on strike for a year and leading them to defeat was nonsense.

The miners’ strike of 1984-85 was a defensive struggle and of a different character to an offensive struggle on pay. It is likely that the miners’ strike of 1984-85 would have developed along relatively similar lines, regardless of whether or not Arthur Scargill was NUM leader,.

Indeed, Scargill and the majority of the NUM leaders, while not shying away from the fight to defend their industry, clearly approached the start of the strike cautiously in 1984 – particularly having lost two national ballots over strike action on pay.

The strike started spontaneously from below. But – like the unofficial action by the postal workers in 2003, which was triggered off by all manner of grievances – it nevertheless reflected the rank and file being to the left of the leadership in understanding the necessary response to the underlying crisis in the coal industry and the Thatcher government’s desire to see off the miners.

More detailed evidence emerging since the strike indicates that top NUM leaders were not as committed or prepared as the rank and file for a long, bitter strike.

The rank and file miner, like the leadership of the Tory Party, understood the full significance of the dispute from its start. It was a battle to the finish where the wider layers of the working class needed to be drawn in to support the miners.

NUM members had enormous trust and confidence in their leadership to ensure such support would materialise.

Arthur Scargill and the NUM leadership did attempt to get solidarity action from other trade unions but generally it was restricted to contacts at the top of the unions, where the Left leaders were unsure or incapable of delivering and the right wing consciously sabotaged any prospect of effective action.

Had the NUM leaders developed contacts before the strike between miners, railworkers, steelworkers, and power workers at a rank-and-file level, as well as at the tops of the unions where possible, then even in the most right-wing-led unions a movement of effective solidarity action could have developed.

Indeed, heroic acts of ‘illegal’ secondary solidarity action occurred on a widespread basis. But, however much heroism was shown by individual workers the Left leaders did not build on the example these workers showed.

And in the right-wing unions every time action looked possible the national leadership consciously undermined it. The NUM leaders had not found or developed sufficient channels amongst the rank and file to reverse this sabotage.

Some union leaders openly sabotaged the strike from the beginning. Bill Sirs (later knighted for his services to capitalism), general secretary of the ISTC, made it clear early on that, despite the existence of a Triple Alliance of railworkers, steelworkers and miners (rechristened the Cripple Alliance because of its ineffectiveness under fire), he would not deliver solidarity action for the miners; even though miners had shown solidarity with steelworkers in their 13-week strike in 1980.

Eighteen weeks into the strike, with many miners’ families already facing severe difficulties, the TUC’s Steel Committee voted against any action which would cut steel production during the strike.

This flew in the face of the mood of ordinary steelworkers, such as those at Llanwern in South Wales who were collecting £2,000 a week for the striking miners.

Right wing break ranks

ON 29 March, the rail, road, transport and seafarers’ unions called on their members to block all movements of coal (a call they did not sufficiently enforce). Within 24 hours, Sirs had broken ranks and accused the miners of threatening his members’ jobs and said he would not see his members “sacrificed on someone else’s altar.” This was from a man who had misled his members to a bitter inglorious defeat in 1980, which led to over 70,000 steelworkers being sacked by British Steel.

To reinforce the point Sirs and his executive agreed that ISTC “would handle fuel supplies, ‘scab’ or otherwise, from any source that presented itself”.2

Steelworkers were understandably concerned about losing their jobs given the contracting worldwide demand for steel and the savage job losses their industry had suffered. Had any of the furnaces cracked and collapsed because their temperature dropped too far then inevitably, given that BSC had announced it wanted further cuts in capacity, they feared it would mean the closure of one or more of the big steel plants.

In many strikes ‘emergency cover’ of one kind or another is required to ensure that workers’ interests are protected. Providing coking coal for steelworks at a sufficient level on a ‘care and maintenance’ basis to ensure the plants were not closed down was a legitimate concession, provided it was at a level that did not allow production to effectively continue or even increase.

Unfortunately, rather than trying to undercut any anxieties amongst rank-and-file steelworkers from below, the miners’ leaders at area level made many compromises allowing coking coal to go into steelworks to prevent the furnaces from collapsing, which reinforced Sirs’ argument.

Local NUM leaders were inconsistently providing extra help for the steelworks in their own areas, in fudged agreements, which could not be sustained or be effective during a long strike. At a later stage this brought them into conflict with Scargill’s plans, which rigidly wanted to stop all coal deliveries into steelworks.

Mass pickets at steelworks were then necessary during the strike because of the criminal strikebreaking of the ISTC leadership. Had a Left leadership controlled the ISTC, then undoubtedly steelworkers themselves through their union would have policed agreements and miners would have been freed to picket power plants and build solidarity in other areas.

The right-wing leaders of the unions in the power industry, John Lyons of the power engineers’ union and Eric Hammond of the electricians union, EEPTU, initially used the lack of a national ballot as an excuse for their inaction.

By the time of the TUC Congress in September, it was clear that whatever resolutions were passed they were going to openly sabotage any attempts to assist the miners.

Eric Hammond was booed when he said the TUC’s pledges, which were passed overwhelmingly, were “dishonest and deficient.” John Lyons of the power engineers was even more brutal about the meaninglessness of the TUC’s decisions: “We will not do it. Our members will not do it. I predict that other workers in the industry will not do it.”3

As treacherous as these statements were, they were an accurate reflection of the right wing of the TUC’s inability to deliver support. John Monks, later to become TUC general secretary reported to the TUC seven weeks after their Congress resolutions supporting the miners on 7 November that “union efforts to block the vital oil supplies had ‘little discernible effect’. That there was little likelihood of ‘crucial fuel shortages at the generating stations’ [and] that in the absence of any further talks scheduled between the main parties ‘prospects for an early settlement of the dispute are remote’.” 4

Regrettably the Left leadership of the NUM and other unions did not adequately come up with a strategy to assist the Left and overcome the sabotage of the right wing.

Another opportunity was to present itself in September for bringing about a miners’ victory – the Nacods strike ballot. In the meantime, how were the different sections of the Left responding to the challenges of this testing dispute?

NOTES

1 Strike, 385 days that shook the nation, Sunday Times Insight Team, p75

2 ibid, p85

3 ibid, p146 ibid, p22.