THE MINERS came closer to victory than they could scarcely have realised in October-November 1984. A number of memoirs, including from Thatcher and MacGregor themselves, subsequently confirmed this.

Thatcher recalled the danger she faced at the time of the threatened Nacods strike, when hardline NCB bosses MacGregor and Cowans had insisted that Nacods members had to cross picket lines and go into work, even if a pit was solidly on strike. This incensed the moderate Nacods leaders who were under great pressure from their rank and file who clearly wanted to do more for the miners than sit at home waiting for the strike to end.

A ballot of Nacods members saw them deliver an 82.5% yes to strike action and a series of NCB miscalculations and incompetence threatened to bring out the Nacods members, which would have stopped every pit in the country working, including in Nottinghamshire.

As one government insider said: “A bandwagon might begin to roll in Mr Scargill’s favour.” Nine years later, Thatcher described this crisis period for her government: “We had got so far and we were in danger of losing everything because of a silly mistake. We had to make it quite clear that if it was not cured immediately then the actual management of the Coal Board could indeed have brought down the government. The future of the government at that moment was in their hands and they had to remedy their terrible mistake.” 1

Again, ten years later, Frank Ledger, the Central Electricity Generating Board’s director of operations, recounted how they had only planned for a six-month strike and that the situation at this time was verging on the “catastrophic”.2

Militant suporter Jon Dale visited Ratcliffe power station, near Nottingham, a few years after the strike. An engineer told him how, in October 1984, their coal stockpile looked as big as ever from the road. But behind, it had all gone. Small emergency diesel generators were being run flat out around the clock, while the main coal-fired generators were just run for peak demand.

Ultimately, the key factor that defeated the miners was not their lack of militant, even revolutionary spirit in the face of the most sustained vicious state onslaught on them and their families; nor was it lack of support from the wider ranks of the working class. And it was not the mistakes that the leaders of the NUM made at national and area level – although some of these were of significant importance later in the strike.

The absolutely crucial factor in the ultimate defeat of the strike was the treacherous and cowardly role of the trade union and Labour leaders. But even without their support the miners came closer to defeating Thatcher than they knew.

From an early stage, right-wing leaders inside the unions were playing a consciously strikebreaking role. Initially this was done more secretively and underhandedly than was to be the case later on in the strike.

This conscious sabotage can be difficult to overcome, given the dead hand these so-called leaders can lay upon the workers’ movement. But it is not impossible that even the most entrenched of these right-wing leaders can be overturned and removed as has been shown in unions like Amicus and the PCS.

In 1984 they represented a conscious strikebreaking force playing on the fears and prejudices of the most backward section of workers. The ‘new realists’ played on the idea that nothing could be done to stop Thatcherism and the only option left was to submit and accept privatisation, anti-union laws and the onslaught of neo-liberalism – described as Reaganism and Thatcherism in those days.

They passively accepted the ruling class’s right to manage and run society, which meant riding roughshod over all the gains the working class had made through their trade unions in the previous two centuries.

This certainly did not inspire workers with much confidence and was not fought against by most of the Left trade union leaders. They lacked confidence in the working class and mistakenly blamed them for the crimes and defeats of Thatcherism.

Snatching defeat from the jaws of victory

TONY BENN recalls in his diaries that, while the wider working class was rallying in support of the miners, the Left union leaders had begun squabbling about how to support the miners from 1 April onwards, less than a month into the strike.

The Left leaders had become accustomed to leading shorter, sharper strikes in a relatively easier period and were in no way prepared for the big battles of the 1980s against a more determined, brutal ruling class.

Their inability to lead a resistance and their failure to mobilise against the biggest threat and challenge faced by the trade union movement since the 1920s squandered nearly all that had been built up by workers in the intervening decades.

The Left union leaders had been conditioned in an era where they could gain concessions by negotiation and compromise – particularly over pay and conditions. With the growing strength of the trade union movement in the 1950s and 1960s, its influence reached a point in Britain that many had not believed possible. This union density in the working population and workers’ influence over their jobs had mainly arisen in a gradual way from the prolonged economic upswing after the second world war.

Whilst there were the big set-piece struggles and strikes it was predominantly the prolonged economic boom that gave workers confidence to demand more and to threaten action if the management didn’t give it. In the 1950s and 1960s the strategy and tactics of union leaders became a process of negotiation and compromise with management, using the threat of calling the workers out if management tried it on too much.

Militant made the points many times in that period that Britain’s bosses were buying industrial peace at the cost of future economic and social ruin for the capitalists.

This was a period of continued economic decline for British capitalism, which inevitably would lead to bitter clashes between bosses and workers as the capitalists attempted to increase their profitability by reducing the share of wealth going to the working class.

During the 1970s – particularly after the simultaneous world economic downturn of 1974-75 –the capitalist class began to attack workers’ conditions won in the post-war period; both on the shopfloor and the social gains won through the welfare state.

The struggles of the early 1970s – particularly the miners’ strikes of 1972 and 74 – exerted elements of workers’ control over management decisions unsurpassed since. But later in the 1970s, the tactics that had proved effective earlier, such as mass picketing and secondary, solidarity action, were being put more to the test and winning fewer victories.

Grunwick – the two-year-long struggle for union recognition of predominantly Asian women workers, despite mass pickets of tens of thousands, including the presence of right-wing Labour cabinet ministers – was ultimately defeated.

Similarly, the so-called ‘winter of discontent’, was a formidable show of strength from union members dissatisfied with the Labour government’s wage freeze policies and their union leaders’ accommodation with it. Nevertheless, the right-wing Labour leaders disingenuously blamed the union members’ justified strike action for the defeat of the deeply unpopular 1974-1979 Labour government and of bringing in Thatcherism. This criticism sent the Left union leaders into retreat.

Thatcherism had been ushered in precisely by that Labour government when it carried through huge cuts in public expenditure at the behest of the International Monetary Fund, which gave the Labour government a financial bail-out package in the economic crisis of 1976 provided the government carried out IMF-dictated austerity measures.

Thatcher’s election in 1979 was to usher in an era of class battles not seen since the 1920s as British capitalism attempted to recover its ‘right’ to hire and fire free from any union influence. Thatcher and her cabinet were, however, not as powerful as the history books portray.

Their ultimate success in beating the miners to usher in a reign of economic and social terror, was only achieved with the class collaboration of the right-wing union leaders and the inability of the Left leaders to use the latent power of the working class.

Should Scargill have settled?

GIVEN THE clear inability of the Left union leaders to deliver the sort of solidarity action needed and to take on Thatcher, was there any other course open to the miners? Should they have avoided struggle at that time and perhaps waited for a better period? Was it possible if they had accepted the NCB’s definition of pit closures in July 1984 that such a strategic retreat would have left them in a better position to temporarily slow down the pit closure programme, deprive Thatcher of her ‘industrial Falklands’ and live to fight another day? Should they have settled on the same terms as Nacods did in November – as Arthur Scargill suggested he was prepared to in January 1985?

The evidence from other industries at the time was that the so-called tactical flair of the right-wing union leaders, such as in steel, or compromise deals of Left leaders fared no better, with tens of thousands of jobs lost.

Clearly, at certain stages of the dispute the personal character of Thatcher, MacGregor and Scargill played a large part in whether or not there could have been a settlement.

But, as was shown subsequently, once the balance of class forces had shifted in their favour, Thatcher and the Tories were out to destroy the mining industry and the mining unions. After the strike they arrogantly tossed aside the Nacods’ deal negotiated in October, leading the Nacods leaders to threaten another strike.

Thatcher particularly made it clear that she was not prepared to settle on any terms and intervened at key points later in the dispute to scupper any prospect of the NCB negotiating a deal behind her back. Inevitably, even if the miners had suffered a partial defeat this would not have been enough for her.

She made it clear that the miners – like the Liverpool councillors – “had no respect for her position” and wanted them crushed to show that militancy would not pay. Towards the end of the strike when it became clearer that they were likely to win, the Tories wanted to use Scargill as a latter-day Braveheart like William Wallace, as an example to others who dared to take on Thatcher: “As one government minister observed: ‘Our leader will not be satisfied until Scargill is seen trotting round Finchley tethered to the back of the prime ministerial Jaguar’.” [Finchley was Thatcher’s parliamentary constituency]3

Thatcher clearly understood she was fighting a battle for the whole of the ruling class to neuter the trade unions, to remove socialist influence from the Labour Party and to re-establish management’s right to manage and to hire and fire in the workplace. Unfortunately, none of the Left leaders, with the exception of Arthur Scargill, saw it in such clear class terms.

Although the memoirs of her government ministers tend to over-emphasise a high degree of unity against making concessions to the miners – as opposed to the splits over concessions they made to Liverpool council. However, this probably reflected their confidence in the preparation that the Tory government had made for a miners’ strike, the fact that the timidity of the Labour leadership and the majority of the trade union leaders posed them no serious problems during the dispute and that no serious, sustained second front opened up at any stage. If the dockers or Nacods had come out for a longer period or if a 24-hour general strike had materialised, then it is more likely that cracks would have opened up in Thatcher’s government.

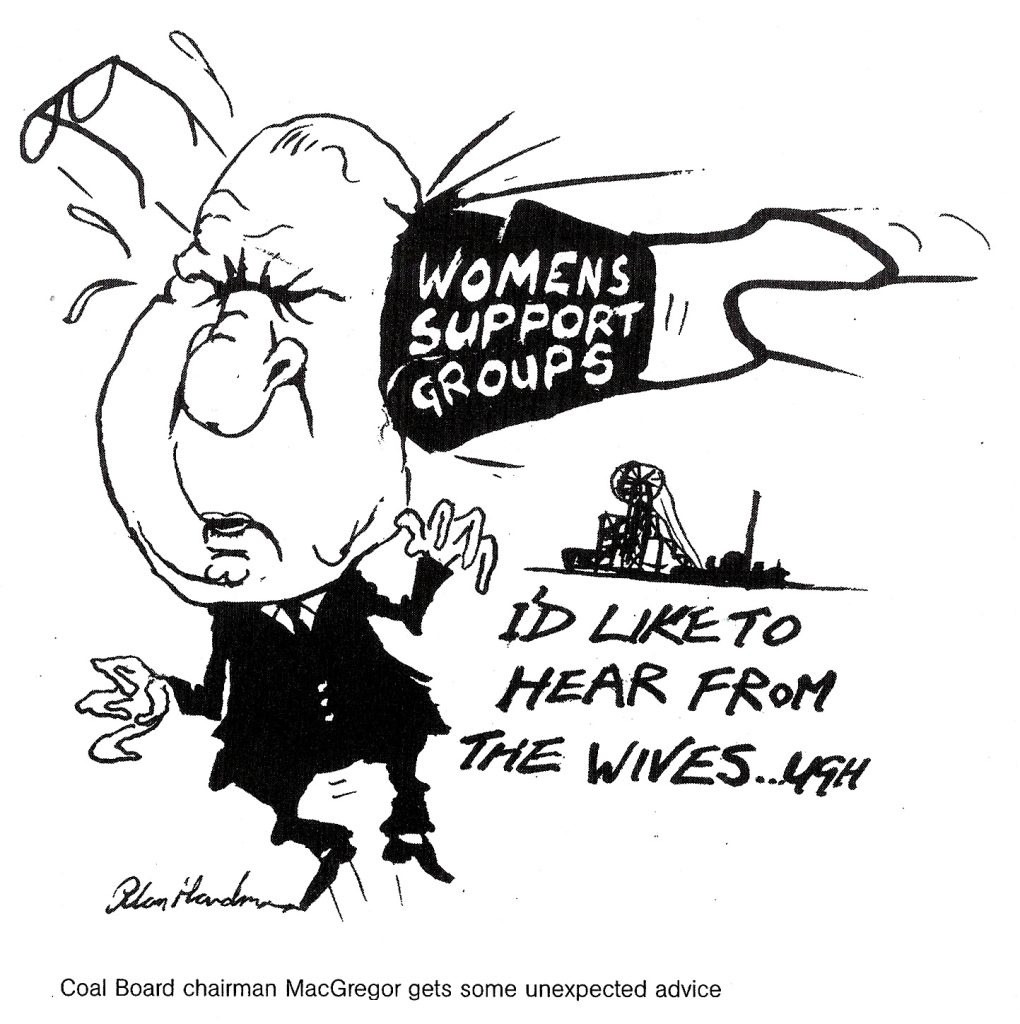

However, there were serious splits and wobbles within the NCB and between MacGregor and Tory energy secretary Peter Walker. Many NCB officials and managers were initially opposed to the hard line being foisted on them by the government and later on, at certain key stages, ineptitude and tactical blunders caused huge rifts inside the NCB. At one stage, MacGregor was effectively removed as the front man for the coal board.

Cracks open in the NUM

INSIDE THE NUM there was a high degree of unity in the areas where the strike was solid at the start of the strike. The right wing in the union, whilst disagreeing with Scargill and the Left’s tactics, would not have dared venture opposition to the strike such was the strength of feeling against the Tory pit closure programme.

However, at local level as the strike wore on, a number of serious splits opened up, particularly after Orgreave and the back-to-work movement developed. At the same time, what has been clearly revealed by Seumas Milne and others is that the state’s security services were hard at work inside the NUM doing their utmost to undermine and discredit the miners’ struggles.

However, all the efforts of the state, including extensive phone tapping and the use of agents provocateurs like Roger Windsor, who was the chief executive of the NUM during the strike, would not have resulted in the defeat of the miners or been able to take advantage of weakness or splits inside the union if the struggle had been going forward.

Clearly, from September onwards there was a leading layer in the NUM, with Kim Howells and Terry Thomas from the South Wales NUM, along with McGahey in Scotland, who were looking for a settlement. Scargill, sensing more accurately the mood of the rank-and-file miners against any sell out, was opposed to settling in the marathon negotiations that took place that month, that looked close to coming to a deal accepting the coal board’s definition of when a pit should be closed.

Correctly, he realised that in the use of the words “where a pit cannot be beneficially developed” the coal board wanted to add was a catch-all clause that would give them carte blanche to close a pit. Under the Plan for Coal a pit would only be closed if all reserves had been exhausted or if it was geologically unsafe. Even the Times editorialised at the time that beneficially “is not an innocent word. It symbolises the division between two philosophies.”

Even the Sunday Times Insight team recognised the obstacles being thrown in the NUM’s path: “While it was easily the best offer made to Scargill in the course of the dispute, it is important to recognise that it would still have represented a retreat.” 4

Had the new wording been accepted then not only would the majority of striking miners have seen it as a sell-out but inevitably it would have meant that the NUM would have been drawn into another large-scale confrontation with the NCB and government sooner rather than later. Or, it would have seen widespread localised struggles against pit closures, where pits would have been sliced off salami style without any possibility of a national or even area fightback being mounted.

This was certainly what happened after the miners returned to work in March 1985. The exhaustion of the year-long battle meant there was little energy and resources left to mount an effective fight, even though the best activists tried valiantly to stop pit closures using argument and mobilising local communities – but the threat of strike action by the national NUM was a spent force.

It is possible that the NUM may have been in a state of less exhaustion and weakness if it had beat a strategic retreat in July, September or October 1984, which may have left it slightly stronger to fight future battles. However, without the ability to bring in other unions behind their struggle it is difficult to see if they could progress any further forward against stopping pit closures. In July, it was a clear a second front was opening up as the dockers took strike action.

At the same time, it is likely that a majority of NUM members would have rejected a return to work on those conditions, holding out and hoping – as Arthur Scargill described it – for “General Winter” to come to their aid.

Wounded but not slain

IN THE winter of 1984-85, the miners came close to bringing about the elusive power cuts, which could have caused enormous problems for the Tory government. Unfortunately, by then they were running out of money (intensified by the seizure of the union’s assets, which were handed from an undemocratically appointed judge to an undemocratically appointed auditor), unable to step up the picketing that was needed at the power plants. The leadership of the union was exhausted of ideas – apart from holding on – to step up the action needed. Even then, it still required efforts to get to the rank-and-file power workers below their rotten right-wing leadership (who were more than happy to see the NUM hung out to dry).

For instance: “At St John’s colliery in Mid-Glamorgan, the 33-year-old lodge secretary Ian Isaac, had made his own clear-eyed assessment, as the funds diminished and the effectiveness of the pickets, never overwhelming, steadily ebbed away. A Militant supporter, who had written his diploma thesis at Ruskin College, Oxford, on the fabled radicalism of his home town, Maesteg, his whole philosophy revolved around a belief in the power of the well-organised worker, but he had looked at the signs this time and drawn his own conclusions: ‘The strike was all done on a haphazard basis. We should have billeted our men in towns where power workers live and really worked at getting to know them and convincing them. We reached the stage where we didn’t even have the money to travel to see the power station people. By November we were logistically beaten’.” 5

By then the Left leaders had adopted an air of passive resignation, at best stepping up the financial and personal assistance to miners and their families but unable or incapable of providing any display of working-class action against the increasingly sharp Tory offensive.

As the winter dragged on and Christmas approached the working class of Britain and internationally showed the most marvellous solidarity with the miners. Hundreds of thousands of pounds were raised and gifts of food and toys for the children came from every continent of the earth.

Although these were very difficult times for the miners and their families very few gave up. In many ways, as many have said since in documentaries and books, the adversity reawakened the solidarity and comradeship of mining communities and with the wider working class.

Anyone who lived through it will never forget that year. In one year, miners, their wives, families, supporters, trade unionists, socialists and Marxists in the Militant tendency learnt more about the role of the state and the need to change the unions and workers’ parties into fighting bodies than could be learned in a thousand books of theory – as important as understanding theory is in seeing it as a guide to action in major working-class struggles.

Had the miners achieved a historic victory against the odds, then with such lessons being learned this would have ushered in a huge sweeping move to the Left inside the workers’ organisations and in society generally.

Their defeat instead steered in a period of new realism, social partnership and sweetheart deals, which the union movement is only beginning to slowly overcome. But the lessons are there for a new generation to learn from as increased working-class consciousness and confidence removes the scars of the miners’ defeat.

NOTES

1 The Enemy Within, Seumas Milne, Verso, London 1994, p17

2 ibid, p16

3 Hugo Young, One of Us, London Pan Books edition 1993, p376

4 Strike, 358 days that shook the nation, Sunday Times Insight team, Coronet 1985, p137

5 ibid p232