THE MINERS’ defeat saw them marching back defiantly behind their banners. Although they were unable to stand up once again to the accelerated pit closure programme, a war of attrition between management and unions took place in many coalfields.

A campaign was also launched to get the hundreds of sacked miners reinstated. Even to this day the victimisation of miners continues, sometimes in the most unexpected ways. In February 2003, ex-NUM official, 69-year-old Jock Glen from east Scotland, was summoned to attend a meeting at the US consulate in London over his request for a visa to enter the USA on a family holiday because he was arrested during the miners’ strike 20 years ago.

In some mining communities the scars of division still remain. Ian Whyles, a North Derbyshire striking miner and Militant supporter, now a Socialist Party member, has barely spoken to his son since the strike ended. His son returned to work halfway through the year-long strike. Even then, Ian “went to speak to him and told him he was old enough to do what he wanted to do. But I reminded him that he had to remember the strike would one day come to an end, but that the community would still be here”… but the real turning point came when “I saw him with a UDM badge on [the Union of Democratic Mineworkers – the breakaway scab union in Nottingham] and that’s when we really fell out.” (1)

A battle is over but the war continues

MANY AREAS only reluctantly went back to work; incensed at the Tory government and angry and bitter at the Labour and trade union leaders who let them down. The acceleration of the pit-closure programme led to a social blitzkrieg in many of the former mining communities, where drug addiction, chronic long-term unemployment, poverty, crime and other devastating social problems became rife. Eventually Thatcherism went rampant after the defeat of the miners but strong echoes of the miners’ strike were to resonate in other big struggles during the Thatcher years: such as the Wapping printers’ dispute; the P&O strikers and most notably in the poll tax struggle, led by Militant supporters, which ultimately led to Thatcher’s downfall.

Dizzy with her own success, however, Thatcher presided over a policy of massive deindustrialisation of British industry and further impoverishment of significant sections of working class and middle-class people. Thatcher thought the benefits accruing to the British economy from North Sea oil would sufficiently offset the loss of manufacturing industry. But, even immediately after the strike, Tory ministers were privately fuming at how little gratitude was shown towards them for defeating the miners:

“For months after the strike was over, ministers often alluded in conversation to the strange ingratitude of the British public… When the strike ended there was no full-throated roar of approval of the kind which had been heard, almost universally, when the Argentineans surrendered in Port Stanley.” (2)

Whilst Thatcher and her acolytes would have preferred the approval, nevertheless, as Hugo Young observed: “The truth was that however muddy the surface waters, the deeper currents flowing out of the miners’ strike carried her in the directions she wanted to go.” (3)

Witch-hunt against the miners and Militant

LABOUR LEADER Neil Kinnock also found the flowing of this tide to his advantage in intensifying the witch-hunt inside the Labour Party against the miners’ leader Arthur Scargill, against the Militant-led Liverpool city council leaders and against Militant supporters inside the Labour Party.

Kinnock, contrary to convention, spoke twice at the Labour Party conference in Bournemouth in 1985 – each time to attack the Left. Firstly he used his main conference speech to attack Scargill indirectly and Liverpool city council head on. Then he replied to a debate on the miners’ strike to attack Scargill and rule out any retrospective legislation to reinstate or support victimised miners.

To Kinnock and his cronies this was all part of the campaign to root out militancy and ‘modernise’ the Labour Party – a codeword for accepting the free-market policies of Thatcherism. This began the process of transforming Labour into an openly pro-capitalist party, like the Democrats in the USA, which has led to the ‘Thatcherism with a grin’ of Blair today.

However, Kinnock’s rapid shift to the right did him no favours on the British electoral field. Despite claiming that militancy was an electoral liability – flying in the face of the evidence of Labour being 5% ahead of the Tories during the miners’ strike and the growing support for Labour in Liverpool – Kinnock and his modernisers like Peter Mandelson, Charles Clarke and Patricia Hewitt went on to spectacularly lose both the 1987 and 1992 elections.

Had the miners won in 1984-85 then it could have seen Thatcher weakened and possibly removed from office, with a Tory defeat at the subsequent general election. The defeat of the Tories was something Kinnock never achieved for all his spin and slick presentation – it took the mass movement of the anti-poll tax struggle, led by Militant, to get rid of Thatcher.

As the effects of the 1980s economic boom wore on, Labour had to wait until 1997 to return to office. The less than inspiring Tony Blair won a landslide (in seats but not in votes) due to the amazing hatred that had built up for the rampant, corrupt, and sleazy Tories over the intervening 12 years. The effects of the miners’ defeat rang loudest in the official corridors of the trade union movement. After the miners’ strike the union leaders began a rightward march that was only halted a few years ago with the election of the ‘awkward squad’.

This class-conciliationist mood at the top did not reflect the growing anger of the rank and file of the trade union movement or the wider working class generally.

Certainly, until the end of the 1980s, although there was a weakening of union structures and a (justified) lack of confidence that the union leaders would mount effective action in defence of union members, the defeat of the miners did not result in a spontaneous big bang that smashed the trade unions.

The trade unions were never completely smashed, as Thatcher had hoped for, despite the craven cowardice and betrayals of the right-wing union leaders. More correctly, there was a gradual corrosion of union structures and a continued deterioration in confidence in the right-wing union leaders.

Even the huge ideological impact the collapse of Stalinism had in the 1990s did not result in the end of trade unionism or socialist ideas, as we have seen with the resurgence of both in recent years. Rather, the effects of the 1990s were a throwing back of consciousness on political and trade union ideology; including a weakening of belief in the solidarity of workers taking collective action. On a number of occasions big struggles broke out against employers taking the cosh to their workforce. In general, these were more localised struggles (although they did attain a certain national significance, like the Liverpool Dockers’ strike in the 1990s) but not so much the idea of trade unions taking effective national industrial action.

Social devastation of mining communities

FOR THE miners and their families, however, the result of the strike’s defeat has been devastating in many areas. Yet, despite that, most of the miners who stood out for the whole 12 months of the strike would not change anything about what they did. This applies also to the miners’ wives who became politicised during the strike and have never looked back.

Dave Nixon, a 27-year-old miner in 1984, looking back at the strike in a BBC2 documentary in 2004 summed up how many miners recall the mixture of sadness and pride they still feel: “Following the colliery band we marched back to the pit through the community we fought for, not with our heads held high but bowed low in sorrow. I remember clearly the pride, elation, bravery, fear, sadness and sorrow; every emotion that one would expect to experience in a lifetime, brought together during the 12-month strike and looking back I truly say, no regrets.”

The tens of thousands of ordinary miners who stuck out for the whole 12 months can feel pride and will be an inspiration to future generations looking for examples of workers’ willingness to struggle. It was not through lack of determination or fighting spirit on the part of these miners and their families and supporters that their struggle was defeated.

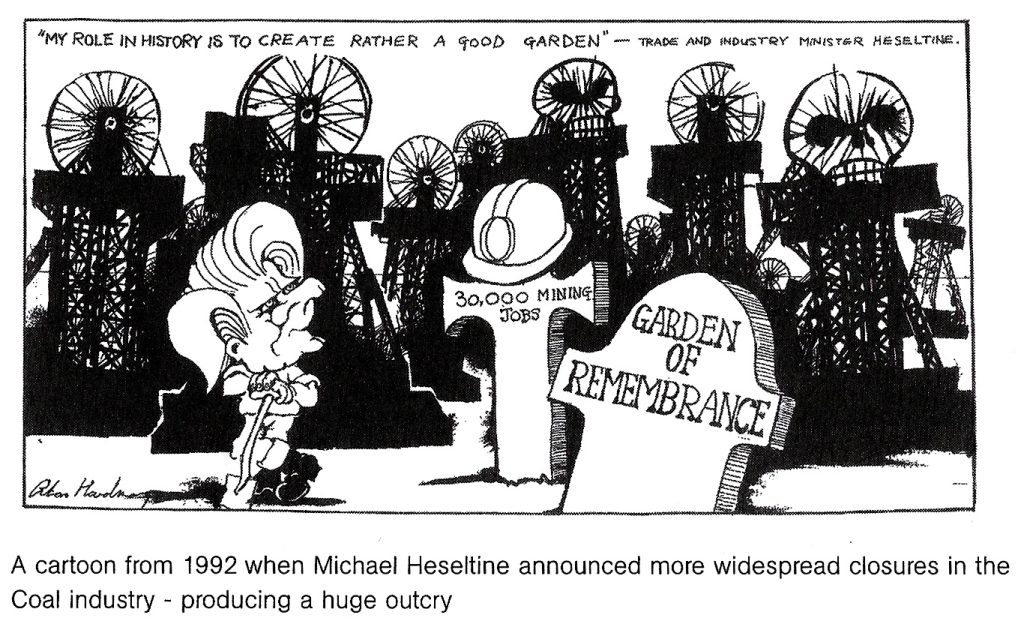

The example that these miners had given led to a huge public outcry in 1992 against Tory cabinet minister Heseltine’s proposals for a massive further cut in deep-mined coal and the loss of over 30,000 mining jobs.

A tidal surge of anger swelled up when all the miners’ predictions about what the Tories were prepared to do to their industry was graphically borne out. Massive demonstrations took place in London, where all sections of the population came out in support. Combined with their support for the miners came a growing hatred of the Tories after the economic debacle of Black Wednesday4 and the anger at the corruption and sleaziness of the Tories which was then starting to unfold.

A National Union of Teachers rep at Holland Park school, west London, recalls how teachers came out at his school in support of the miners: “The NUT group at my secondary school voted to take half-day strike action so that we could join the march through west London – all completely outside of the anti-trade union laws, of course. I believe some schools in Camden also took action that day.

“Our group of teachers and students made the short walk through the side streets and joined up in Kensington Church Street. There was an incredible crescendo of noise as we came out into the main body of the march. From all points around, from shop doorways, windows and balconies, hundreds and hundreds of shop workers, bank staff, waiters from the restaurants, ordinary shoppers and residents were shouting their support. Many had improvised banners and placards against the pit closures. It was the same in Kensington High Street. It was almost unbelievable, like a huge outpouring of support, from workers primarily, but also from many who could not be classified as working class by any stretch of the imagination. After all these were some of the richest streets in Britain, and hundreds of miles from any pit. It’s where the upper class shop, eat and live. Maybe, some of it was guilt because it was now clear that what the miners had said all along was now being proved true; but I think it was more than that.” 5

Arthur Scargill correctly called for the TUC to call a 24-hour general strike in support of the miners and there’s little doubt that the public mood would have supported the action against the increasingly despised Tories, who had just narrowly won the 1992 election against Kinnock. However, he also spoke on platforms with CBI representatives, echoing the ‘broad alliance’ policy that the CP had advocated in 1984-85.

Again the TUC did nothing concrete but desperately pleaded with government ministers. The fact that Heseltine did a body swerve (reminiscent of Thatcher in 1981) owed everything to the growing mood of public anger and nothing to the inaction of the TUC.

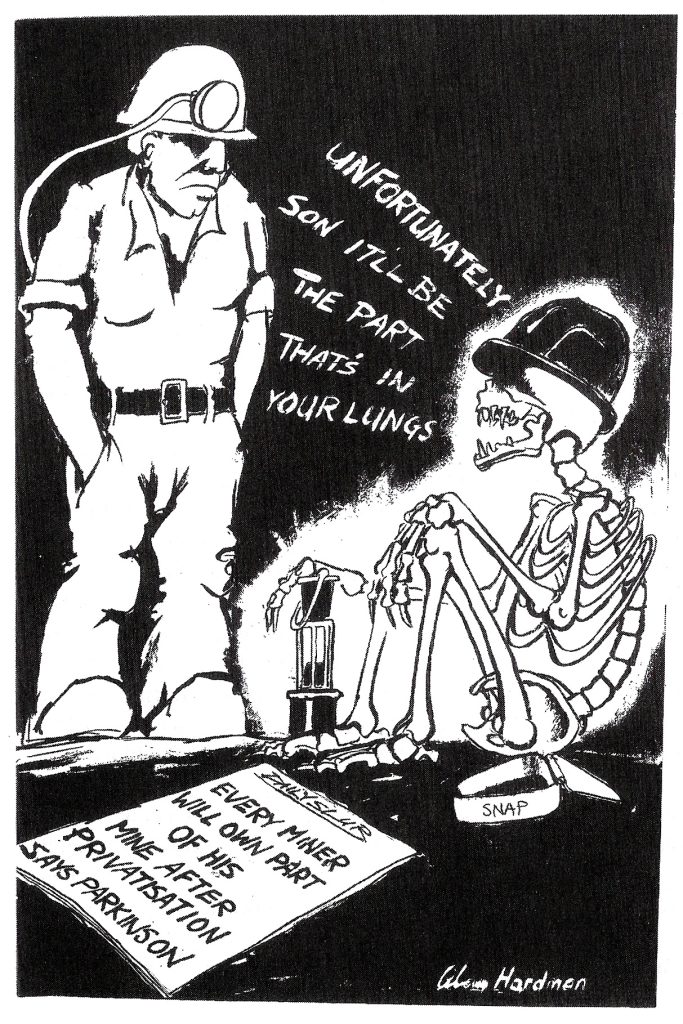

The respite against pit closures was only temporary. And under Blair’s New Labour government the continued rundown of the coal industry has continued apace. Within a few months of its election in 1997 a secret report was leaked to the Independent newspaper revealing that Labour planned to let RJB Mining destroy 5,000 mining jobs (RJB was the privatised successor to British Coal which later became UK Coal). In July 2002 came the announcement that the Selby super-pit complex, which had only opened 20 years previously and was heralded as the future of mining, was to close with the loss of 2,000 jobs. Again the refrain was that “deteriorating geological conditions and continuing financial losses” meant the pit had no prospect of “becoming viable”.

In 2003 the UK coal industry employed just over 9,000 people – approximately 6,500 of those in deep mines in only 12 pits; the other 2,500 are employed in 49 opencast sites. In 2002-2003 total UK coal production was 28.9 million tonnes, of which 15.8 million came from deep mines – overall this was a fall of 13% in coal production from the previous year and is less than 18% of what was produced 20 years ago. The UK imported almost as much coal as it produced in 2003 – 28.6 million tonnes, although this was down from the record figure of 35.3 million tonnes in 2001 – a sure sign that many more pits could and should have been kept open, even by the logic of capitalist economics.

Ironically, there has been an increase in demand for coal for electricity generation in the last few years because of the increasing costs of oil and gas as supplies become scarcer. If ever there was an example of the short-sightedness of British capitalism – particularly Thatcher and her conscious decision to deindustrialise Britain to weaken the working class and the trade unions – then the run down of coal is the prime example.

Unbending and unbreakable

ALL OF the miners’ opponents have suffered ignominy in one form or another. Thatcher was ousted after the debacle of the poll tax; Kinnock never won a ballot in the form of a general election and went on to be a European Commissioner on a millionaire lifestyle, frequently under attack from allegations of corruption in the EU section he presides over; MacGregor left the NCB under a cloud and died in 1998 and Robert Maxwell, the Daily Mirror owner who accused Scargill of corruption mysteriously fell off his boat and drowned when his attempts to corruptly swindle the Mirror workers out of their pension rights came to light. The UDM has dwindled as a discredited force inside the declining coalfields. It has recently been involved in scandals, accused of arranging lucrative deals from miners’ compensation, which has allowed UDM leaders to earn salaries and bonuses of at least £150,000 a year.

All of the union leaders who undermined the miners’ struggle have all gone and will in no way be remembered in contrast to Arthur Scargill. His predictions about the butchery of the coal industry during the strike and the need to struggle were proved presciently true.

He made mistakes during the dispute. And although he was correct to break from Labour in 1997 he made some fundamental political mistakes over the way his Socialist Labour Party was launched and run. However, whatever mistakes he made during the strike, no one could deny his refusal to buckle under the Tories and class enemy’s pressure. He stood firm during the strike, an inspiration to the striking miners themselves, and has never renounced the conduct of the strike or seen it as anything less than justified.

Although he is an isolated figure on the fringes of the Left today, the example he gave during the strike still resonates. It was no accident that the first ‘insult’ the Labour government reached for in trying to denigrate the firefighters during their dispute in 2002-2003 was accusing the union’s members of being “Scargillites”.

Whilst the Socialist Party would have disagreements with Scargill on this or that strategic or tactical decision during the strike, we believe that identifying strikers today with the heroic example of the miners in 1984-85 will come to be worn as a badge of pride amongst workers involved in new struggles. It will be seen as an example of being willing to go to the end in defending the interests of the working class. But, as Militant said at the end of the strike in 1985: “Scargill did prove to be ‘unbreakable’ but an unbending will by itself is insufficient.” (6)

The legacy for today

THE MINERS’ strike of 1984-85 is rich in lessons about the determination of working-class people to struggle. But it is also rich in lessons about the strategy and tactics that trade unionists need to apply.

It also shows the need for a wider political understanding in working-class organisations about the need to assess the possibilities of success of a strike, the options available, the balance of class forces, as well as surveying the stage of development of the trade unions and workers’ organisations. Arising from that comes the need to transform and retransform the workers’ organisations into militant class-struggle bodies with mass involvement of the rank and file, linked to a leadership armed with a clear Marxist understanding and programme to change society. The magnificent firefighters’ and postal workers’ actions in 2003, despite the timidity of their official leaders, showed a new willingness to struggle and a refusal to be intimidated by threats and anti-union laws.

Today’s generation and future generations in Britain will increasingly look to change their unions into fighting organisations. They will look back on the British miners’ strike of 1984-1985 and seek to learn the many lessons from that heroic struggle of how best to effectively challenge capitalism and replace it with a new, socialist society.

Building a movement to achieve these goals would be the best way to honour and avenge the defeated miners who fought so valiantly in the 1984-1985 Great Strike for jobs.

We believe young workers will increasingly look to the ideas of the Socialist Party and Marxism and advocate our programme for changing the unions and society, including the following demands:

- For the unions to take immediate action to implement their current minimum wage demands, as a step towards a legal minimum of £8 an hour. No exemptions

- For an annual increase in the minimum wage, linked to average earnings. For a minimum income of £320 a week

- A range of policies to achieve full employment including the introduction of a maximum 35-hour week without loss of pay

- Employment protection rights for all from day one of employment

- Reject Welfare to Work; for the right to decent benefits, training or a job without compulsion

- Scrap the anti-union laws

- Trade unions to be democratically controlled by members

- Full-time officials should be regularly elected and receive the average wage of the workers they represent

- Renationalise the privatised utilities under democratic working-class control and management

- Major investment into a integrated system of energy production that meets the needs of the people and the environment

- A plan of sustainable energy production, including an environmentally friendly use of coal, to be drawn up between energy workers, trade unions and representatives of society generally

- For massive investment into the development of sustainable energy resources – including solar, wind and wave power – in order to reduce fossil fuel use

- For the urgent phasing out of all nuclear power, with guaranteed, well-paid, alternative employment for the workforce

- A massive increase of public spending into healthcare, housing, education, childcare, leisure and community facilities

- Take into public ownership the top 150 big companies, banks and building societies that dominate the economy under democratic working-class control and management, with compensation paid only on the basis of proven need

- An end to the rule of profit

- Campaign to form a new mass party of the working class.

- For a socialist plan of production

- For a socialist society and economy run to meet the needs of all whilst protecting our environment

NOTES

1 Worksop Guardian, 13 February 2004

2 Hugo Young, One of Us, Pan edition, London 1993 p375

3 Ibid, p377

4 On this day, 16 September 1992, interest rates were increased twice in one day to a record 15% to vainly try and keep Britain in the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) after huge speculation against the pound. It was seen as one of the most spectacular failures of economic policy by a British government.

5 Interview with Bob Sulatycki. Many other examples that illustrate this movement were also carried in Militant at the time

6 Militant, issue 739, 8 March 1985