In the Paris Commune in 1871, for a brief but heroic few weeks, the working class took power for the first time in history. In the immortal words of Karl Marx, the masses ‘stormed heaven’. In extremely hazardous circumstances, Parisian workers attempted to re-organise society, to abolish exploitation and poverty, before falling beneath a vicious counter-revolution. Cecile Rimboud, Gauche Révolutionnaire (CWI France) outlines the key role that working-class women played in this historic struggle.

If the development of a society can be judged by the extent to which women are involved in it, that is certainly the case with a revolution. In 1871, women – especially women workers – played a huge role in the Paris Commune, despite significant hindrances. These heroic women workers swept aside forever the idea that their emancipation could happen outside of the class struggle.

Women’s labour had already played a very important role in industrial production in the 1860s in France and it had developed very rapidly. In 1871, 62,000 jobs out of 114,000 industrial jobs were held by women. Many thousands of female workers worked outside of industry – as home-based workers, laundresses, day labourers (cleaners). Women, as well as child labourers, were very poorly paid, earning a lot less than men, and this was used by the bosses to drive all wages down.

Women workers had to suffer horrendous sexual harassment from the bosses, and from some of their male co-workers, in the factories and workshops; sexual blackmail over employment was common. The wages were so low that many women had to prostitute themselves. In her Mémoires, one of the Commune’s most famous figures, Louise Michel, wrote: “The proletarian is a slave and the most enslaved of all is the wife of the proletarian. And what about women’s wages? Let us talk a little about that: it is no more than a decoy”. Women workers’ conditions were truly atrocious.

Victorine Brocher, a boot-stitching worker who was very active in the defence of Paris later, wrote in her Memoirs of a Living-Dead Woman: “I saw poor women working twelve and fourteen hours a day for a derisory salary, having old parents and children whom they had to leave behind, locking themselves up for long hours in unhealthy workshops where neither air nor light nor sun ever penetrates, for they are lit with gas; in factories where they are shoved in like herds of cattle, to earn the modest sum of two francs a day, earning nothing on Sundays and holidays”.

“Often, they spend half the night repairing the family’s clothes; they would also have to go to the wash-house to wash their clothes on Sunday mornings. What is the reward for these women? Often anxious, she waits for her husband who has been lingering in the neighbouring drinking den and only comes home when three quarters of his money has been spent… The result: abject poverty or prostitution”.

During the final years of the Empire, some women workers had been agitating against these terrible conditions. The most politically advanced of them, who would later rally to the International Working Men’s Association (IWMA – the first international), started to be active in trade unions. Nathalie Le Mel, a Breton binder and leader in the binders’ union, joined the IWMA after the 1865 strike that won equal pay, regardless of sex, for Parisian binders.

Reactionary views

These activists had many opponents, and they were not only bosses. The majority of the workers’ movement then, including the politically heterogeneous IWMA, did not support women workers. Amongst others, Jean-Baptiste Proudhon, a self-declared anarchist and member of parliament after the 1848 revolutionary upheavals, had a very reactionary position. Proudhon theorised that women were inferior to men.

In Justice in the Revolution and the Church (1860), Proudhon scandalously wrote: “In itself, the woman has no reason to exist; she is an instrument of reproduction… The woman remains… inferior to the man, a sort of medium between him and the rest of the animal kingdom… The man will be the master and the woman will obey”.

The common position that “women should stay at home” was defended by the majority of the French delegation at the IWMA Congress of 1866, although some leaders, like Eugène Varlin and Antoine Bourdon, opposed this. They moved a resolution at the Congress stating that: “Women need to work to live honourably, therefore, we must seek to improve their work instead of abolishing it”. The resolution was defeated. The French workers’ movement then was not defending better conditions for women workers but the abstract call for the ‘abolition’ of women’s labour. In this regard, Varlin and Bourdon’s resolution was progressive. Such figures in the French workers’ movement, not least Marxists, played a key role in the struggle for women’s rights.

Léodile Champaix, who took the alias André Léo, was a member of the IWMA at that time, and a writer. She commented: “On this question, revolutionaries become conservative”. She pointed out how ironical it was for those who pretend to struggle for freedom to defend “a small kingdom for their personal use, each in their own homes”.

This reactionary view remained the dominant position in the workers’ movement, as well as amongst the majority of the working class of France, at the time. Hypocritically, the dominant ideology condemned women’s labour and demanded of women to be mere housewives deprived of all rights. At the same time, society rendered this role impossible for working-class women: they were already drawn into heavy industry and suffered terribly from exploitation and poverty.

Opposing bourgeois views

In the second part of the 1860s, strikes over pay took place throughout the country. Here and there, papers and journals were published to discuss women’s rights. One example was the bi-monthly Women’s Rights. It aimed at discussing “the moral, intellectual and civil emancipation of women – as daughters, as wives and as mothers” but not financial emancipation, and not women as workers!

These journals were mostly produced by bourgeois men and women, who did not encourage women, in general, to organise or take political action. On the contrary; in July 1869, the Women’s Rights newspaper commented: “We do not tell them [women] that the time has come for them to claim their share of those political rights … because their education has not prepared them for the special virtues required for political action”. How wrong were they proven to be by the heroic action of the Parisian women workers not two years after this outrageous declaration.

On the other hand, Karl Marx and scientific socialists had always supported the rights of women and women workers. And although they were in a minority in France at the time, they did everything they could to aid women workers to organise and fight. This was not only for emancipation and equality but for the workers’ movement to change their position and defend the women of the working class.

A young collaborator of Marx was Elisabeth Dmitrieff. She was an activist in Russia before immigrating to Switzerland where she helped found the Russian section of the IWMA. She was only 21 years-old when she went to Paris to build support for the ideas of scientific socialism, particularly among women. The emancipation of women, she maintained, would happen through the emancipation of the whole proletariat. One of the tasks was thus to stir up the class consciousness of Parisian women workers to draw them into the revolutionary fight.

Female socialists were not concerned only by matters regarding the condition of women workers. The activists, members of the IWMA, and others were also among those who were most serious about the success of the Commune itself.

André Léo, for instance, was relentless in her attempts at convincing the people of Paris and members of the Commune that the isolation of the struggle in Paris and the alienation of the peasantry would be fatal. On 9 April 1871, she wrote: “In the provinces, there is danger, there is a disaster. Paris at this moment hates and curses the provinces and the provinces hate and curse Paris. A mountain of lies and calumnies has been raised between them”.

Together with Auguste Serrailler, a member of the IWMA and the Commune, Léo worked, alas unsuccessfully, to get a decree passed on the abolition of mortgage debts, which would have raised great support among the peasantry: the mortgage debts of small landowners had skyrocketed to a total of 14 billion francs.

Women in military defence of Paris

In his famous narrative, History of the 1871 Commune, Pierre-Olivier Lissagaray wrote that on 18 March, the beginning of the insurrection, when the new capitalist government of Adolphe Thiers had abandoned Paris after France had been defeated in war by Prussia: “Women were the first to act, as in the days of the [1789] revolution… Those of the 18 March, hardened by the siege, did not wait for the men – they had had a double ration of misery”. Women started organising quickly. A battle was waged for women to be officially incorporated into the military defence of Paris.

Of course, women had not waited for any official orders to defend Paris and the revolution; thousands had already participated in its defence during the siege by the Prussian army. Several female defence organisations were established. Louise Michel, André Léo, and others organised ‘ambulances’ (paramedic services), and the distribution of food and clothes.

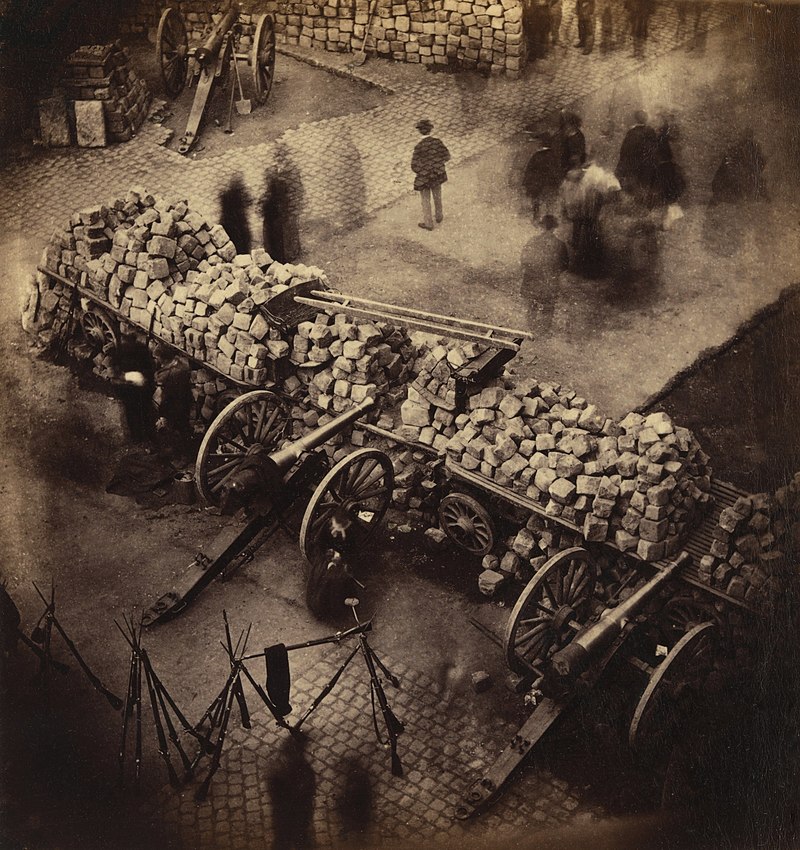

On 8 May, Léo, in a quite pessimistic article entitled The Revolution Without the Woman, protests against the hostility of the National Guard commander General Dombrowski and others to integrating the women paramedics of Montmartre in the army and on the outposts: “Do you know, General Dombrowski, how the revolution of March 18 was made? By women. At early dawn, troops had been sent to Montmartre. The small numbers of National Guard who guarded the cannons of the Saint-Pierre square were taken aback, and the cannons were being removed”. Louise Michel related: “Women covered the cannons with their bodies”.

Lissagaray writes: “The attitude of the women during the Commune was admired by foreigners and infuriated the Versaillais”, those in Versailles where the Thiers government had withdrawn to. Ten thousand women workers fought during the ‘Week of Blood’. The Twelfth Legion of the Commune even had a female contingent.

The Women’s Association

Several women’s organisations were created in the heroic days of the Paris Commune. Most notably on 11 April the Union des Femmes pour la défense de Paris et les soins aux blessés (Women’s Association for the defence of Paris and care of the wounded), was created. Its members had put themselves at the disposal of the Commune and were ready to “fight and conquer, or die”.

On the founding of the Union des Femmes, a manifesto was published in the form of an address to the Executive Commission of the Commune, published in the Official Journal of the Commune on 13 April. The address stated: “The Commune represents great principle in proclaiming the annihilation of all privilege, of all inequality, and by the same (principle) is thus committed to taking into account the just claims of the entire population, without distinction of sex – a distinction created and maintained by the need for antagonism on which the privileges of the dominant classes are based”.

It demanded the necessary means of organisation for women to be able to be truly involved in the revolution, such as rooms in each district where they could meet and organise their political activity.

This was agreed to by the Commune. Louise Michel is one of the most well-known figures of the Commune. But it is worth noting that even if she demonstrated great bravery, her political views were not socialist and she, therefore, did not play any role in the attempts to form trade unions or women workers’ organisations like the Union des Femmes. This was very active and well organised and was mainly led by women workers who displayed tremendous courage.

On 18 May, the Association’s executive commission was still convening an assembly of women with its famous Call to Women Workers. The aim was to constitute trade union branches, whose elected delegates would, in turn, form the Federal Chamber of Women Workers. The Association, with its headquarters in the beautiful town hall of Paris’s Tenth Arrondissement (an administrative district), held daily meetings in all arrondissements and organised about 300 members.

Elisabeth Dmitrieff, in particular, was aiming at using the Women’s Association to encourage the political organisation of women in the IWMA to fight for socialism. Despite the absence of women in the Commune itself, in some arrondissements women had been integrated into the administration; in the Ninth Arrondissement, a woman named Murgès sat on the council.

The Women’s Association waged a ferocious struggle against bourgeois women who, through posters and papers, espoused defeatist and demoralising propaganda. On 3 May, a poster stated: “Women of Paris, in the name of the fatherland, in the name of honour, finally in the name of humanity, demand an armistice!” – in other words, accept the rule of the capitalist government in Versailles.

The Women’s Association responded on 6 May with a poster: “It is not peace, but war at all costs that the workers of Paris come to demand… The women of Paris will prove to France and to the world that they too will know… how to give their blood and their lives, like their brothers, for the defence and triumph of the Commune!… Then, victorious, able to unite and agree on their common interests, men and women workers, all in solidarity, by the last effort, will destroy forever all vestiges of exploitation and exploiters!”.

Huge inspiration

Many very progressive measures for women, albeit short-lived, were gained during this two-month long revolution. The closure of brothels was won. The Commune banned prostitution, considered as “a form of commercial exploitation of human creatures by other human creatures”. Common-law partnerships were officially recognised. Widows of National Guardsmen killed in action were granted the payment of a pension, whether officially married to them or not, and their children, whether legitimate or ‘natural’, were recognised on the basis of a simple declaration.

Women pleading for separation from partners could also be granted the payment of a pension. Education and childcare were revolutionised. The church and the state were separated, hospitals and schools were also made secular. Male and female teachers won equal pay.

The most important concern was the shortage of work. All the women’s associations demanded work from the head of the Commune’s Labour and Trade Commission, Léo Frankel. He endorsed the proposals of the Women’s Association, including the requisitioning of abandoned workshops and the organisation by the Women’s Association of cooperative workshops for women to work in. Dmitrieff, in particular, was afraid that if the Commune failed to take bold measures to employ and provide living wages for women, they would “go back to a passive and more or less reactionary state that the previous social order had created – fatal and dangerous for revolutionary interests”.

Tragically, all the progressive measures were cut across by the bloody onslaught on Paris from Versailles starting on 21 May.

Women fought heroically during the Paris Commune and its ‘Week of Blood’ at the end of May. As Karl Marx put it: “The real women of Paris showed [themselves] again – heroic, noble and devoted… joyfully giving their lives on the barricades and on the place of execution”. The editor of the newspaper, Le Vengeur, commented: “I’ve seen three revolutions, and, for the first time, I’ve seen women getting resolutely involved, women and children. It seems that this revolution is precisely theirs and that by defending it, they are defending their own future”.

Thousands had died during the ‘Week of Blood’, but the heroism persisted. “Defeated but not vanquished”, were the words of Nathalie Le Mel, deported to New Caledonia along with Louise Michel and thousands of others. How impressed we can be, seeing such determination! The fight of the scientific socialists like Dmitrieff and others to form women workers’ organisations in the face of such adversity is truly an example and a treasured jewel in the armoury of the world workers’ movement.

What a tremendous source of inspiration the Paris Commune and these women can provide for all those today who seek to end discrimination and exploitation of women and all the oppressed! The women of the Commune began to show the way. The emancipation of women can be achieved only through a common, united struggle of the working-class – men and women alike – aiming at freeing labour from capital and in this way ending all forms of exploitation.