The Communist Women’s Movement inspired tens of thousands of women following the Russian revolution. Christine Thomas looks at the latest volume in an ongoing series regarding the Communist International that pulls together previously unpublished material about this relatively unknown international women’s movement in the period 1920-22.

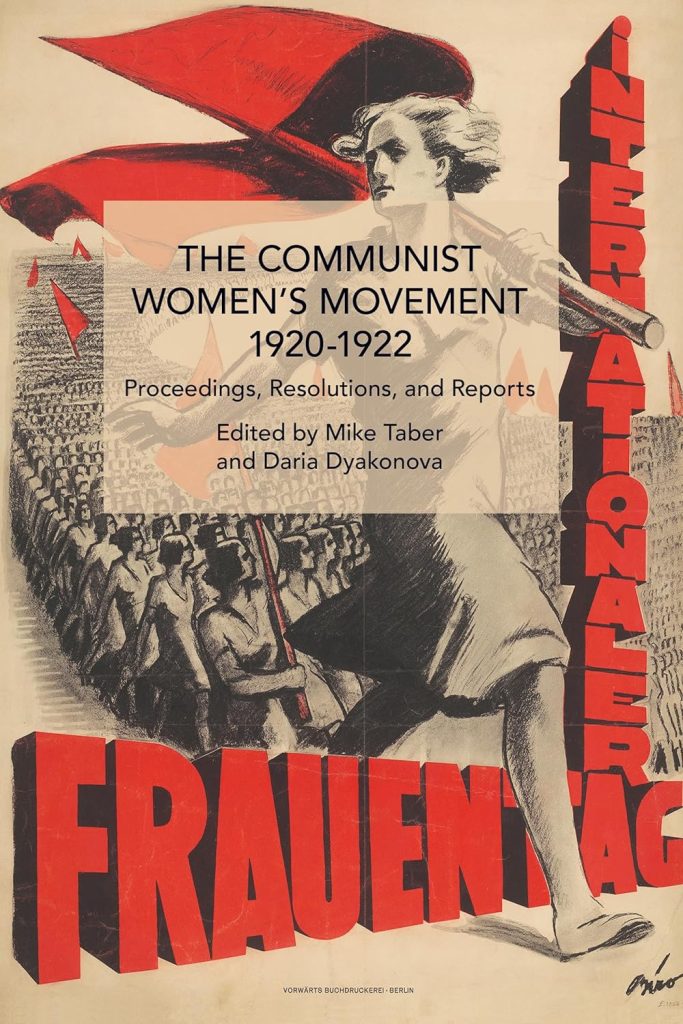

The Communist Women’s Movement 1920-1922: Proceedings, Resolutions, and Reports, Edited by Mike Taber and Daria Dyakonova, Published by Haymarket Books, 2023, £40

“On the evening of 30 July 1920… a chorus of women’s voices singing The Internationale fills the streets of Moscow. Women proletarians, in an orderly and elated procession celebrate the opening of the International Conference of Communist Women at the Bolshoi Theatre. At about 8 o’clock that evening, the hall is filled from top to bottom… The stage is occupied by women delegates from Germany, France, Britain, the United States, Mexico, Austria, Denmark, Sweden, Hungary, Finland, Norway, Latvia, Bulgaria, India, Georgia, the Caucuses and Turkestan, as well as representatives of various organisations and institutions welcoming the First International Conference of Communist Women”.

It’s hard for us today to appreciate the profound international significance of the Russian revolution in the immediate post-revolutionary period, but this report gives a glimpse of the inspirational effect it had on socialist women. Those in capitalist countries struggling to end their double oppression as workers and as women now had a living example of what the overthrow of capitalism could achieve.

Inessa Armand, one of the organisers of the first conference and head of the Russian women’s department (Zhenotdel) was able to report that as a result of the revolution women now had full political and civil rights, equal to men. “Socialisation of production and expropriation of the capitalists and landlords leads to the complete destruction of every form of exploitation and every economic inequality”. “In Soviet Russia the working woman at a factory or plant is no longer considered little more than a hired slave, but is a full-fledged leader, on the same level as the male worker”.

“The situation with relation to the family and marriage is quite similar. The Soviet power has already established equal rights for husband and wife. The power of the husband and father no longer exists. The formalities of marriage and divorce have been brought down to the minimum, reduced to simple written statements”. Protection for pregnant and nursing mothers, public nurseries and kindergartens, social dining halls and kitchens, repair shops and communal laundries, were all transforming working women’s lives.

Mobilising women

At the first Congress of the Communist International, held in 1919, a resolution drafted by Russian revolutionary Alexandra Kollontai had stated that “the complete abolition of the capitalist system can be fully achieved only through the common, united struggle of working-class men and women”, and that every Communist Party member should urgently “work forcefully and energetically to win proletarian women to its ranks”. The Guidelines for the Communist Women’s Movement noted: “It is impossible for the proletariat to win through revolutionary mass actions and in civil war without the decisive participation of women of the toiling people… They constitute half – among the most advanced peoples even more than half – of working people”. “Without the active and conscious participation of the broadest masses of Communist-minded women such a deep-going, massive transformation of society, its economic base, and all its institutions, is impossible”.

The first task of the Communist Women’s Movement (CWM) was to mobilise women within the Soviet republics to defend the revolution – which at the time of the first conference was still threatened by internal and external counter-revolutionary forces – and for women to be fully involved in building the new society. The second parallel task was to win working-class women in the capitalist world to the communist movement and the struggle to overthrow capitalism. This was essential not only for their own liberation but for the consolidation of the revolution in Russia itself, an economically underdeveloped mainly peasant country, ravaged by war and civil war, which needed the economic collaboration and solidarity of the working class in the more advanced global economies.

But how was the Communist Women’s Movement to awaken women’s ‘revolutionary spirit’, their energy, activity, initiative and self-reliance? Only by recognising that while working-class women share many of the same economic concerns as working-class men they also face specific problems related to their gender. As comrade Gerten (Sturm) pointed out in her report to the first conference of the CWM, they were not just a “working slave” but also a “household slave”, and carrying the burden of motherhood. If a woman was working twelve hours, travelling for another hour to get home and then had her “housekeeping work” to do, “the woman has no spare time to read the papers, to go to meetings and to express her ideas”.

Nadezhda Krupskaia from Russia commented on the way that women are socialised in capitalist and feudal societies to take on a more ‘passive’ role, lacking confidence in their own abilities. “I have often had occasion to observe how timidly a working woman is at a meeting at first, not daring to say a word”. But, she added, “gradually she gains interest in the whole thing, and afterwards becomes a valuable worker in the labour movement as a whole”. At the second CWM conference, in 1921, a delegate from the German Communist Party (VKPD) also stressed that “with respect to women… as soon as they are convinced that fighting is essential they will devote themselves to the cause much more audaciously than men”.

Convincing those potential and essential women fighters for socialism could not be left to chance, however. It required a conscious and organised approach by the Communist parties affiliated to the Communist International and by the International itself. It necessitated new methods of propaganda and approach especially geared towards reaching, recruiting, educating and giving confidence to women to play a full role in the struggle to change society.

Special structures

With that aim in mind, resolutions to the first Communist Women’s Movement conference urged the Communist parties to set up national and local women’s committees that could organise and oversee their work amongst women in a planned and consistent way. These would not be separate bodies but integrated into and under the leadership of the democratic decision-making structures of the party. Their role was to supplement the general work of the party, not to substitute or duplicate it.

Of course, although the resolutions were quite detailed about how the women’s structures should function, they were not immediately applicable to every section of the International. In Soviet Russia, the model on which the Communist Women’s Movement Guidelines were based, there was a mass Communist party that had carried out a successful overthrow of capitalism and landlordism, and was simultaneously fighting off a vicious counter-revolution by the Whites and imperialist forces and striving to build a society along socialist lines. The German and Czech parties also had a mass base, while others were still mainly small propaganda organisations, wielding much less influence amongst the working class. Some of the parties were legal, others had to function clandestinely. The CWM resolutions outlined the general aims but with an emphasis on flexibility of structures and methods tailored to specific national experiences.

Sections were urged to organise public meetings and carry out ‘agitation’ to attract new female members with specially prepared material – newspapers, articles in the main party press, pamphlets, leaflets etc. At the same time, they had a responsibility for helping to politically educate and develop female members into ‘cadres’ and leaders of the party – through the general structures and through special women’s discussion meetings and groups. Their aim was to encourage the overall political development of women members and not just their interest in specific issues of concern to them because of their gender.

At an international level an International Women’s Secretariat (IWS) was established, nominated at the congress and then confirmed by the Executive of the International. Initially based in Moscow, it was moved to Berlin at the beginning of 1922 to aid communication with the national sections. These were encouraged to establish ‘international correspondents’ who would liaise with the IWS, sending in campaign material and regular reports of their work among women.

Women workers

Every national women’s section was expected to prioritise ‘agitation’ amongst working women, as it was the working class, with its decisive role in the capitalist production process, which would need to place itself in the leadership of the revolutionary movements for the destruction of the old societies and the construction of the new. A Russian delegate explained that even in pre-revolutionary Russia, where the overwhelming majority of women were peasants and “only one-tenth were working women”, “we nevertheless made it our aim to work exclusively among them”.

The first world war had drawn women into the factories and workplaces in their tens of thousands, replacing men fighting at the fronts. In closing the conference of the Women of the East, Leon Trotsky spoke of data he had seen claiming that in Japan, for example, there were more working women than working men. A delegate from Latvia at the first CWM conference described the revolutionary effect these processes had on working women “drawn into workers’ organisations en masse”. Two million out of nine million trade union members in Germany were female, reported a German delegate, but, she added, “the number of women holding responsible posts is insignificant”.

When the war ended, however, working women came under attack from multiple fronts. Revolutionary movements had been defeated in Germany, Austria, Hungary, and later Italy because, as the ‘Report on the Participation of Women in the Struggle to Win Political Power’ put it “at the head of the movement stood reformist parties” instead of the “class-conscious and militant Communist Party” that had existed in the form of the Bolsheviks in Russia. Women workers were competing for jobs with demobbed men in a situation of economic crisis, rising unemployment, and a capitalist class hell bent on shifting the burden of the crisis onto the working class through increased exploitation and dismantling of social welfare.

“In every country where the proletariat has not taken power through revolutionary struggle”, declared the leading German Communist Party member Clara Zetkin, “the slogan again rings out loudly: ‘Women get out of the workplace! Women back to the home! It finds an echo even in the trade unions”. But a delegate described how in Austria, Communist Party women had fought the right-wing union leaders to keep women in the metallurgic industry on lighter work, albeit on lower wages. “This incident brought new adherents to our ranks”, she explained.

Fighting the post-war cost-of-living crisis and the desperate suffering of working women ran like a red thread through the work of the different national women’s sections, becoming the central issue for International Women’s Day in 1922. “What will we and our children eat? How will we clothe ourselves in the face of monstrous inflation? Where are the healthy homes that will shield our children from tuberculosis, rickets, and early death? How can I increase my inadequate wages, and how can I pay my taxes? How can I do both my housework and my factory work? What will become of us when we’re old and sick? Where do we get the means to pay for the midwife, for nappies, for food and care for mother and child? How do we live if we lose our jobs? Who helps the family when the provider is jailed for daring to oppose deteriorating working conditions?” “All these questions demand an answer”, declared the International Women’s Day appeal at the first women’s correspondents’ conference in 1922. Sentiments that will resonate strongly with working-class women today.

The second correspondents conference of the CWM stated that “all struggles… even struggles for minor bread-and-butter demands – have to be led in a manner that serves the great ultimate goal: preparing women in the workers’ united front for the fight to overthrow capitalism”. In Germany, women were involved in workers’ committees to control prices. They fought against extending the working day and allowing night work for women. They demanded “Integrate all unemployed in production! Keep the eight-hour day! Fight against any wage cuts; raise wages to at least subsistence levels! Equal pay for equal work by men and women! Maintain and expand workplace safety measures for men and women! Fight for humane care of mothers and children!”

Campaigning issues

The International Women’s Secretariat produced appeals for International Women’s Day, now firmly established as 8 March, and helped to coordinate one of the most important and successful international campaigns, Aid for Soviet Russia, which was able to draw broad layers of women into collecting material help for those suffering from famine and want in the Volga and Urals regions in particular, as a consequence of war, civil war and drought.

The Secretariat also circulated a thesis on abortion and another on campaigning around the issue of prostitution. The Communist Women’s Movement guidelines demanded “economic and social measures to fight prostitution; for hygienic measures against the spread of sexually transmitted diseases; for an end to the housing of prostitutes in barracks, to their supervision by vice squads, and their social ostracism. End the sexual double standard for men and women”.

The Soviet government legalised abortion in state hospitals in 1920. In the capitalist countries the most important campaign on reproductive rights was waged in Germany, where the Communist Party fought against Paragraphs 218 and 219 of the Penal Code, under which women who had an abortion could face five years in prison, while those carrying out a termination could be imprisoned for up to ten years. Twenty thousand women were dying annually from illegal abortions in Germany. As the memorandum from the German Communist Party’s Women’s Secretariat explained, the anti-abortion law “in reality opens the doors of the clinics to women of higher social status, while proletarian women are delivered into the hands of quacks and denounced by police snitches”.

Mass meetings were organised in many German cities, mainly on the initiative of grassroots communist women. Campaigning around the slogan ‘Your body belongs to you’, the party recognised that, “as long as society is not capable of rendering motherhood materially possible for women under civilised conditions, it has no right to demand of them that they take on the sufferings and burdens that spring from motherhood”. They drew up a motion for their MPs to present in the Reichstag (the German national parliament), which as well as calling for the repeal of Paragraphs 218 and 219, demanded the establishment of Pregnancy Advisory Centres, hostels for pregnant women, paid maternity leave, nurseries and play schools, and public assistance for unemployed women.

Reform and revolution

Some delegates, notably Nora Smythe from Britain, were opposed to standing in elections, and even campaigning for women’s suffrage, which Liudmila Stal’ from Russia identified as “the disease of ‘leftism’” which Vladimir Lenin had criticised in his pamphlet Left-wing Communism: An Infantile Disorder. A CWM resolution confirmed that standing in elections and electoral agitation amongst women were not simply about “chasing after votes and offices” but “Communist inspiration and education, oriented towards deeds and struggle”; the activity of those elected to parliament “must aim beyond the parliament and call the masses outside parliament to rally for the revolutionary struggle”.

The Communist Women’s Movement was attempting to steer a course between two dangers: on the one side illusions in bourgeois ‘equal rights’ feminism, and on the other an ultra-left rejection of fighting for ‘partial’ reforms under capitalism. Clara Zetkin explained that the campaign for women’s suffrage in those countries where it had not yet been won was a “starting point”, a means and not an end in itself. It could not, as the bourgeois feminists claimed, achieve full equality for women, but was part of the fight to mobilise women into action to achieve liberation through a fundamental transformation of society.

The CWM affirmed that, “The right to vote cannot destroy the original cause of women’s enslavement in the family and society. Introduction of civil marriage… in the capitalist countries does not grant women equality in marriage and does not resolve the challenge of mutual relations of the sexes, so long as conditions persist where women workers are economically dependent on the capitalist and the male wage earner”. “It is not the united efforts of women of different classes that makes communism possible, but rather the united struggle of all the exploited”.

Although the main orientation of the CWM was towards working women in the workplaces, trade unions and cooperatives, it didn’t ignore peasant women and ‘housewives’ who, having to work all day in the home, have “no opportunity for getting a wider outlook on life”, argued Sturm, getting submerged in their “drudgery”. Delegates explained how these women, seeing their misery as individual and not shared, were particularly susceptible to the reactionary influences of the church, nationalists, monarchists and bourgeois prejudices, which could lead them to holding workers rather than capitalism responsible for their problems and even breaking strikes. “Our propaganda and educational work”, said Zetkin, “must be conducted in such a manner as to break down the narrow walls of home life… so that their thoughts and feelings should be outside, with society, on the battlefield of the class struggle”. In Austria members were sent to agitate in the marketplaces and squares, others went door-to-door in order to reach women in the home.

Interestingly, according to Kollontai, ‘intellectual women’ – which was the term the Communists then used to describe social workers, civil servants, local government workers, teachers etc – could assist the struggle “but they cannot be looked upon as an actual power such as that represented by the proletarian women”; a very different situation from today where those sections of women workers have been ‘proletarianised’ to such an extent that they are no longer seen as ‘privileged’, but an integral and powerful section of the working class, at the forefront of many recent strikes and workplace struggles.

Strengths and weaknesses

Delegates reported on the tremendous bravery of working-class and peasant women involved in the struggle. In Lithuania, “women would go to the trenches to bring rations, arms and ammunition. This aid often facilitated the victory of the Red Army”. In Russia, reported Inessa Armand, women workers defended the factories, plants and soviets and also “quite a lot of women workers chose to fight at the front against the White Guards, side by side with the men workers”. According to Sturm, in Bavaria, at the time of the short-lived Bavarian soviet republic during the 1918-19 revolution, “working women set up machine guns in their dwellings, defended the workers’ quarter of the city, fired on the advancing White Guards, and still held that quarter when the rest of the town had already surrendered”.

This activity was carried out at enormous personal risk. Aura Kiiskinen from Finland spoke about how even “the sisters of the Red Cross were mercilessly persecuted. Hundreds of the best and bravest women comrades are still languishing behind prison walls, and the number of new victims of the secret police is still growing”. “Red Latvia”, described Tumu, “fell and the banner of White Latvia was raised over one thousand dead bodies of women and men workers who were shot and massacred”. Even in the USA, reported Ella Reeve Bloor, “one of our women, a grandmother, was shot on the picket line just because she took part in a steel strike”.

While recognising success in involving women in the struggle, there was no glossing over the weaknesses. The report at the second conference of international women’s correspondents, printed in the CWM’s international paper, stated “…our International Communist Women’s Movement is still fairly weak. In most countries the party’s influence on working-class women is very limited. Only small numbers of working-class women are members of the party. In most countries comrades have as yet hardly embarked on conscious and systematic activity in the trade unions at all, let alone considered a special focus on working women. This momentous task still lies ahead of us”.

At the second conference of the CWM, Henriette Roland-Holst of the Netherlands reported that “there are perhaps a hundred women registered as party members, and they have been enrolled by their menfolk. When the men go to party meetings the women stay at home with the children”. A Czech delegate complained that only 20% of the party’s members were women. In France, where the figure was even lower, the Communist Party’s first conference reported that “it is of course impossible to completely overcome the feminism and anti-feminism that have long burdened the French revolutionary workers’ movement”.

Contemporary capitalist commentators and historians are eager to spread the myth of ‘Lenin the dictator’ (see The Real Lenin, in Socialism Today, issue No.274, February 2024) but also ‘Lenin the misogynist’. However, the reality was, as Zetkin declared at the conference of ‘Women of the East’, “Comrade Lenin has made himself the champion of the women’s cause”. That didn’t mean, of course, that the Communist parties could hermetically seal themselves off from the prejudices of society at that time. “We have not received much encouragement from the men”, said Lucie Colliard from France on the question of organising working women in the Communist party. A delegate from Sweden complained, “whenever we need some help in the way of speakers in our meetings for working women, or money for issuing some special pamphlets, we remain without assistance”.

However, the situation could improve. Sturm from Germany at the second Communist Women’s Movement conference spoke about the struggle to convince male comrades that, in a situation of high employment, women should not be considered as competitors but allies in the workplace. By the German party’s third women’s conference it was reported that “this conference heard fewer of the laments (not always entirely unjustified) that male party comrades lacked comprehension of their work and did not give it enough support”.

Building a new society

At the second conference of the CWM, Clara Zetkin explained that “even after capitalism is overthrown… there still remain certain ideas of a capitalist nature in some minds. All these prejudices, all these remnants of the bourgeois way of thinking… must be defeated. Educational work means the rooting out of prejudices”. This ‘educational work’ would be necessary even after the socialist revolution in an advanced capitalist country today, but it was particularly important post-1917 in a predominantly peasant country where much of the population was illiterate.

One of the most inspiring aspects of the Communist Women’s Movement was the work of the Zhenotdel in the Soviet republics in educating and above all convincing women workers, peasants and ‘housewives’ to be fully involved in the defence and extension of the gains of the revolution. Travelling representatives went out to the regions from the Sverdlov Communist University, often employing innovative means such as theatre or women’s clubs with workshops, creches, exhibits and other facilities to encourage women’s participation. ‘Repair shops’ allowed women in rural areas, who otherwise would not have attended party meetings, to come together and repair clothes while discussing and being introduced to the communists’ programme. Particular attention was paid to reaching ‘Women of the East’ (areas in the Caucuses and Central Asia where many Muslim women lived) and overcoming the cultural and religious barriers that held them back from supporting and taking part in the struggle for revolutionary change.

Women’s sections registered volunteers who would be seconded to Soviet departments as ‘interns’ for a few months. A system of women’s delegates elected from workplaces and neighbourhoods and the organising of delegate conferences – “schools of communism” – by the women’s sections formed a link between party and non-party women. According to Kollontai five to six thousand of these a year were organised. Through this work – the meetings, assemblies, discussions, conferences – tens of thousands of women were mobilised to defend the revolution during the civil war; were involved in the supervision and direction of economic production; helped draft new laws relating to women; participated in the soviets and the setting up and running of nurseries, communal dining rooms, literacy schools, hospitals, housing collectives and all the social institutions that the Soviet government was establishing. Kollontai reported to the second Communist Women’s Movement conference that women’s sections had set up 217 nurseries in 12 ‘gubernias’ (provincial administrations).

However, the important work of the Communist Women’s Movement was short-lived. With the rise of the Stalinist bureaucracy, rooted in the economic underdevelopment and global isolation of the revolution, many of the social gains for women in the Soviet Union were rolled back. While the Soviet government under Lenin had attempted to surmount the very real economic constraints on vital communal services, these were used by the Stalinist bureaucracy as a reason to close or run down nurseries, creches, dining rooms, etc. Abortion, homosexuality and prostitution were recriminalised, divorce made more difficult. The family unit and women’s role as mothers were glorified as the bureaucracy embarked on a programme of rapid and forced industrialisation, requiring a growing workforce and rising birthrate. At the same time, the hierarchical, patriarchal family unit played an important role in instilling and reinforcing the bureaucracy’s need for discipline, deference to authority, and social stability.

As part of this process the Zhenotdel was formally abolished in 1930. The International Women’s Secretariat was transferred back to Moscow in 1924 and downgraded, and the international women’s movement declined in tandem with the degeneration of the Communist International itself, no longer a vehicle for promoting and extending revolution internationally but defending the interests of the Russian Stalinist bureaucracy under the slogan of ‘socialism in one country’. Far from aiming to develop critically minded cadres of an international revolutionary movement, the original goal of the Communist Women’s Movement, the Russian bureaucracy wanted pliant figures who would not challenge their political retreat. Unfortunately that became the role even of CWM pioneers like Krupskaia, Kollontai and Zetkin.

However, the legacy of the Communist Women’s Movement during those three crucial years from 1920-22 lives on, and, taking account of historical differences, provides a fascinating and useful insight for those fighting today for the ending of gender inequality and oppression and the liberation of women through the socialist transformation of society.