China’s ‘Cultural Revolution’ 1966-67

50 years ago the ‘Cultural Revolution’ began in China. Here we carry an edited version of article written by Socialist Party general secretary Peter Taaffe for Militant (predecessor of the Socialist) in February 1967.

Within the last month, events within China have taken a dramatic turn. Reports of fierce clashes between forces for and against Mao Zedong, strikes, allegations of ‘sabotage’, etc. have been splashed across the pages of the capitalist press.

While most reports have exaggerated the picture, what is certain is that the current purge in China is spreading its tentacles to ever more layers of the ruling stratum and indeed is reverberating throughout the whole of Chinese society.

These upheavals are but the latest culmination of the so-called Cultural Revolution. For almost a year now a ceaseless campaign has been conducted by Mao Zedong against the opponents of his ‘thought’.

In the process numerous ‘heroes’ of yesterday have been demoted to ‘capitalist agents’ today. Thus Peng Zhen, former boss of Beijing, along with a host of other luminaries, has been cast out of the charmed circles of the ruling elite. Even the president, Liu-Shaoqi, is currently under attack.

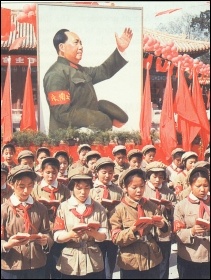

Alongside this has gone the attempt to deify Mao Zedong to the level of god. Bent on stamping his imprimatur on all things, the 22 million-strong Red Guards have run amok within Chinese cities denouncing anything and everything remotely connected with ‘western culture’ or that which faintly conflicts with the omniscience of the ‘leader’.

Culture

We have seen the Red Guards, in the most hooligan fashion and in direct opposition to the Marxist attitude towards culture, destroy priceless books and paintings. Shakespeare, Pushkin, Bizet and Beethoven have all been condemned as “ideologues of the exploiting classes”.

How to explain these upheavals within China? This cannot be done by mere reference to the personal quirks of one man, (irrespective of how all-powerful he may appear) as is the fashion with the capitalist press. On the contrary, these events indicate a profound social crisis which afflicts the very vitals of Chinese society.

In fact the present regime in China has been one of crisis right from the outset. This is reflected in the periodic eruptions in the state, the bureaucracy, agriculture, industry and all aspects of life. It has been characterised above all by a constant policy of zig-zags, a violent veering from one expedient to another.

Given the march to power, and the birth and evolution of the present regime, this could not fail to be so. Unlike the Russian Revolution, the Chinese Revolution of 1944-49 saw not the working class but the Red – predominantly peasant – Army, headed by Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai and their entourage, play the dominant role.

The Chinese Stalinists displayed the fear of the bureaucracy towards any independent movement by the working class. In their eight-point peace programme they unashamedly warned the working class: “Those who strike or destroy will be punished… those working in these organisations (factories) should work peacefully and wait for the takeover.”

And true to their word, any independent action by the working class was met with the most ruthless repression. Contrast this attitude with that shown by Lenin and the Bolsheviks in the Russian Revolution. The Bolsheviks looked towards the working class as the main agent of change and urged “the land to the tillers and the factories to the producers.”

Mao Zedong and the Chinese Stalinists trimmed their ‘Marxism’ to fit the needs of a Bonapartist clique at the head of the peasant armies. They only came to power because of the peculiar combination of forces which came together at that time.

Having learnt his lessons well at the school of Stalin, Mao Zedong, in the fashion of Bonapartism, manoeuvred between the classes and from the beginning constructed a state based in fundamentals on the totalitarian system in Russia.

Nevertheless, the destruction of landlordism and capitalism ensured that the Chinese economy could develop with seven league boots. A tremendous impetus was given to the building of roads, industry, chemicals and all sections of the economy.

In the language of steel, concrete and cement and, to a certain extent, the living standards of the people, nationalisation and a plan demonstrates its superiority over the outmoded system of capitalism; this despite the existence of a parasitic bureaucracy from the beginning.

But given its isolation, the triumph of the revolution was bound to lead to contradictions on a higher plane. The Chinese Stalinists based themselves on Stalin’s conception of ‘Socialism in one country’.

But from the time of Marx, genuine socialists have always viewed socialism as realisable only on a world scale. It is international or it is nothing and, moreover, must be based on technique and production higher than that achieved by capitalism. Marx himself pointed out: “Where want is generalised… all the old crap must revive.”

First and foremost among this ‘crap’ is the state itself. “Want is generalised” to a great extent in China – and with it the unrestricted growth of the bureaucracy. With the masses denied the right to discuss the aims, methods and details of Chinese economy, all the mistakes of Stalinist Russia have been committed on a monumental scale. This accounts for the ceaseless convulsions of which the Cultural Revolution is but the latest.

A number of factors have come together to provoke the present crisis. The severe dislocation resulting from the so-called ‘Great Leap Forward’ caused conflict within the top echelons of the Communist Party.

From the top

Ordained from the top by Mao Zedong, the Chinese nation was dragooned into the lunacy of “backyard steel production”, when workers and peasants were instructed to set up their own furnaces. The result: virtual stagnation in the economy for years.

Such was the case also in the field of agriculture. With the forced march towards complete collectivising of agriculture, they have succeeded in aiming crippling blows at production. Unheeding the lessons of Stalin’s debacle in collectivising Russian agriculture, the bureaucracy brought about a standstill here as well.

The ‘communalisation’ was carried through with the primitive tools used on small plots of land for centuries and without the large scale machines and technique necessary for the working of large units. The peasants reacted to the move with hostility: the consequence being a loss of self-interest and a plummeting of output.

The result of all this has been that grain production is still at the level of 1956 and the bureaucracy has been forced to make a partial retreat in allowing the cultivation of small plots to the extent that the Economist reports: “80% of pigs and 90% of poultry are raised” in this way and “account for more than half of peasant incomes”.

Only a real plan of production drawn up by the masses themselves would be able to develop the economy in harmony, bring about the necessary balance between agriculture and industry and demonstrate in practice the superiority of nationalisation.

Added to this has been the collapse of the ‘international’ policy of the Chinese Stalinists. Despite the demagogy of Mao Zedong, their policy has been based on furthering the national interests of the bureaucracy and not on the interests of world socialism and the working class.

As with the Russian Stalinists, they have attempted to court the support of the national capitalists throughout the underdeveloped world. Thus they were silent at the time of the east African mutinies, which were put down by their friends President Julius Nyerere of Tanzania, President Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya, etc.

In Indonesia, in a situation that was rotten ripe for the overthrow of capitalism, the Chinese bureaucracy instructed the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) to tail-end President Sukarno, the representative of the national capitalists. Upwards of half a million PKI members were slaughtered. The biggest Communist Party in the world outside of Russia and China was sacrificed on the altar of the diplomatic interests of the Chinese Stalinists.

Crisis

These factors among others have provoked the present crisis and are reflected within the Chinese state, among the bureaucracy and in sections of the people themselves. Meeting opposition from a layer of the bureaucracy, Mao-Zedong brought into being the Red Guards as a club by which to beat down and destroy the opposition.

Thrown into a national shell and as the supreme arbiter, he has leaned upon a more backward and younger section of the bureaucracy. As The Times put it: “The conflict… lies between an elite newly established to run the Cultural Revolution, and the old guard bureaucrats entrenched in the Communist Party.”

Like Stalin before him, he has issued quite a few denunciations of the worst excesses of bureaucrats against the “restriction of democracy” – all the better to preserve the position of the bureaucracy as a whole. In turn Liu Shaoqi leaned on a section of the workers, utilising their discontent and demands for better conditions which provoked the formation by Mao Zedong of the Red Rebels (the Red Guards’ adult counterparts) and vicious denunciations of ‘economism’.

In this is revealed the substance of the Cultural Revolution. With sugar-coated words, Mao Zedong and the bureaucracy are willing to use the working class and the peasantry in the inter-bureaucratic struggle. But let them once advance even their own limited economic demands and this is “sabotage” and is attacked as the “vile road of economic struggle.”

Similarly with the question of democracy. It is conveniently forgotten that the Communist Party has held only two Central Committee meetings in four years while the Congresses have been convened only twice since 1949! What hope then is there for the masses to have a say in deciding their own fate under the present regime?

The present massive rallies in Beijing and elsewhere are not socialist democracy. On the contrary, as Leon Trotsky pointed out some thirty years ago, “The democratic ritual of Bonapartism is the plebiscite. From time to time the question is presented to the citizens: for or against the leader.”

Genuine socialist democracy means the democratic control and management of the economy and the state by the working class and the people themselves. It means elected delegates subject to recall and with a clearly defined maximum wage, an armed people instead of the standing army, the right of all working class tendencies which accept the nationalised property to be represented in the workers councils, and all the factors which make for real Soviet power.

None of these exist in China at the present time. Hence the convulsions, contradictions and mismanagement of the economy by the bureaucracy.

With the cancer of a bloated and privileged elite battening itself onto the necks of the Chinese people, the upheavals involved in the Cultural Revolution will be perpetrated and even increased. There is no final solution so long as the bureaucracy maintains its stranglehold. For while it is possible for the Chinese economy to develop despite the blight of the bureaucracy, far from the social antagonisms disappearing they will grow apace with the growth of the economy itself, so long as the present regime exists.