Dave Nellist, Socialist Party national committee

May Day has been a public holiday in the UK since 1978. But its real origins lie in the great struggles in America by working people for shorter working hours at the end of the 19th century, and the martyrdom of union leaders executed 130 years ago.

The centre of the movement for an eight-hour working day was Chicago, where some factories imposed an 18-hour day. An eight-hour law had actually been passed by the US congress in 1868. However, over the next 15 years, it was enforced only twice.

But over that same period workers began to take matters into their own hands. For example, in 1872 100,000 workers in New York struck and won an eight-hour day, mostly for building workers.

In the autumn of 1885, a leading union, the Knights of Labor, announced rallies and demonstrations for the following May – on the slogan of “eight hours for work, eight hours for rest, eight hours for what we will.”

Their radicalism and success in key railroad strikes had led to membership growth. From 28,000 in 1880, the Knights of Labor grew to 100,000 in 1885. In 1886 they mushroomed to nearly 800,000. The capitalists were increasingly frightened at the prospect of widespread strikes.

On 1 May 1886, the first national general strike in American history took place, with 500,000 involved in demonstrations across the country. As a direct consequence, tens of thousands saw their hours of work substantially reduced – in many cases down to an eight-hour day with no loss in pay.

The employers lost no time in executing their revenge. The New York Sun, as direct as its modern British namesake, advocated “a diet of lead for hungry strikers”!

Two days later, on 3 May, 500 police herded 300 scabs through a picket line at the Chicago factory of farm machinery firm International Harvester. When the pickets resisted, the police opened fire and several workers died.

Haymarket

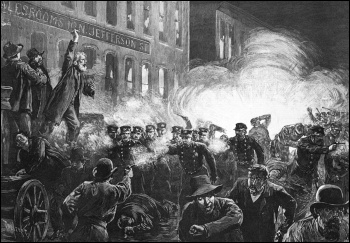

A protest meeting was organised for the following evening in Haymarket Square. Towards its end, in the pouring rain, with only a couple of hundred workers left, the police arrived to break it up.

The meeting had been orderly, but suddenly a bomb was thrown into the ranks of the police. Seven officers were killed and 66 injured.

The police turned their guns on the workers, wounding most of the demonstrators, and killing several. It was never established who threw the bomb – an ‘anarchist,’ or a police ‘agent provocateur.’ At the subsequent trial of the union leaders the prosecution said it was irrelevant, and the judge agreed.

Police raids rounded up hundreds of union activists throughout the country. Eight union leaders were put on trial. Seven of them had not been at the demonstration and the eighth was the speaker on the platform, so none of them could have thrown the bomb.

Legality was never the aim of that trial; revenge was. The Chicago Tribune of the day gave the game away with the headline: “Hang an organiser from every lamp-post.”

The trial began on 21 June. Instead of choosing a jury by picking names from a box – the normal method – it was rigged by a special bailiff, nominated by the prosecutor. He ensured the jury was made up of “such men as the prosecutor wants” – a practice echoed by today’s jury selection in Ireland’s Jobstown protest trial!

On 19 August that jury duly returned a verdict of guilty. Before sentence was formally announced, the defendants were allowed to make statements.

One of the eight, August Spies, a leader of the anarchist International Working People’s Association, made a powerful speech: “Your Honour,” he began, “in addressing this court I speak as the representative of one class to the representative of another…

“If you think that by hanging us you can stamp out the labour movement… the movement from which the downtrodden millions, the millions who toil in want and misery expect salvation – if this is your opinion, then hang us!

“Here you will tread upon a spark, but there and there, behind you – and in front of you, and everywhere, flames blaze up. It is a subterranean fire. You cannot put it out.”

On 11 November 1887, four of the union leaders were executed.

International protests followed. Huge meetings were addressed in England and Wales by Eleanor Marx, George Bernard Shaw, Oscar Wilde and William Morris. 200,000 people in Chicago lined the streets for the funerals.

Day of solidarity

From that day on, 1 May has grown to an international day of solidarity among working people.

In 1889, the founding meeting in Paris of what became known as the Second International passed a resolution calling for a “great international demonstration” to take place the following year. The call was a resounding success.

On 1 May 1890, May Day demonstrations took place in the United States and most countries in Europe.

Friedrich Engels joined half a million workers in Hyde Park in London on 3 May, and reported:

“As I write these lines, the working class of Europe and America is holding a review of its forces; it is mobilised for the first time as one army, under one flag, and fighting for one immediate aim: an eight-hour working day.”

As workers have emerged from tyranny and repression in whatever country, they have adopted May Day as theirs. Its true history will undoubtedly inspire a new generation of socialists, as it has done so often in the past.

- Every year on May Day, the Socialist prints messages of solidarity from across the workers’ movement. Click here to see this year’s record 99 greetings across ten pages, which raised over £5,200 for socialist ideas.