Lewisham 1977: When socialists and workers defeated the far-right National Front

Roger Shrives, Lewisham Socialist Party

The tragic murder of anti-racist protester Heather Heyer by a white supremacist at a far right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, brought back memories to me of another attempted far right march, in London.

40 years ago almost to the day before Charlottesville, on 13 August 1977, the fascist National Front aimed to march through my home borough, Lewisham. Many workers in the borough came from Afro-Caribbean backgrounds. Racist attacks had been growing.

The whole labour movement was under attack as fascism wanted to destroy workers’ rights and democracy. Local black youth, trade unionists and socialists aimed to stop the fascists – and succeeded.

Recession

The right-wing Labour government of 1974-79 failed to tackle the first post-war capitalist recession with bold socialist policies. During 1975 and 1976, wages had plummeted faster than in practically any post-war year.

National Front propaganda made much of this and some working class people voted National Front (and its split-off the National Party) in a council ward election in Deptford in 1976. It was largely through an active campaign, led by the Labour Party Young Socialists (LPYS), with its Militant (forerunner of the Socialist) leadership, that a fascist victory was averted.

Facing the National Front threat in 1977 Labour’s right wing, assorted bishops and Communist Party figures in the ‘All Lewisham Campaign Against Racism and Fascism’ (ALCARAF) campaign wanted to avoid directly confronting the fascists and organised a protest miles from the march.

The LPYS nationally and other lefts voted to stop the fascists, following the example of Cable Street in east London where local workers stopped Mosley’s fascists marching in 1936. When ALCARAF told counter-demonstrators not to go to New Cross to confront the fascists, many marchers saw this advice as splitting the movement and joined the New Cross protest.

4,000 police (armed with riot shields for the first time outside Northern Ireland) were mobilised to help the fascists carry out their march. Protesters’ fears about violent confrontation were greatly lessened by good stewarding and good organisation, linking arms and acting together against the National Front and the police horses, batons and riot shields.

As Militant (19 August 1977) said, the LPYS contingent “were the most disciplined section of the counter-demonstration. Positioned where the police charge began, it set a shining example of how to exercise effective anti-fascist action.”

The police charge tried to crush the counter-demonstrators but a barrage of bottles, bricks and other materials was thrown at the fascists when they appeared. The National Front were humiliated – reduced from a swaggering triumphalist march to a dejected gaggle. Many National Front activists did not even try to march.

Foiled

Despite the failure of the trade unions’ and Labour Party leadership to mobilise their forces, a few thousand protesters had foiled the plans of the National Front and the police. It gave confidence to young black people and to the LPYS to hold mass anti-racist meetings in cities like Birmingham.

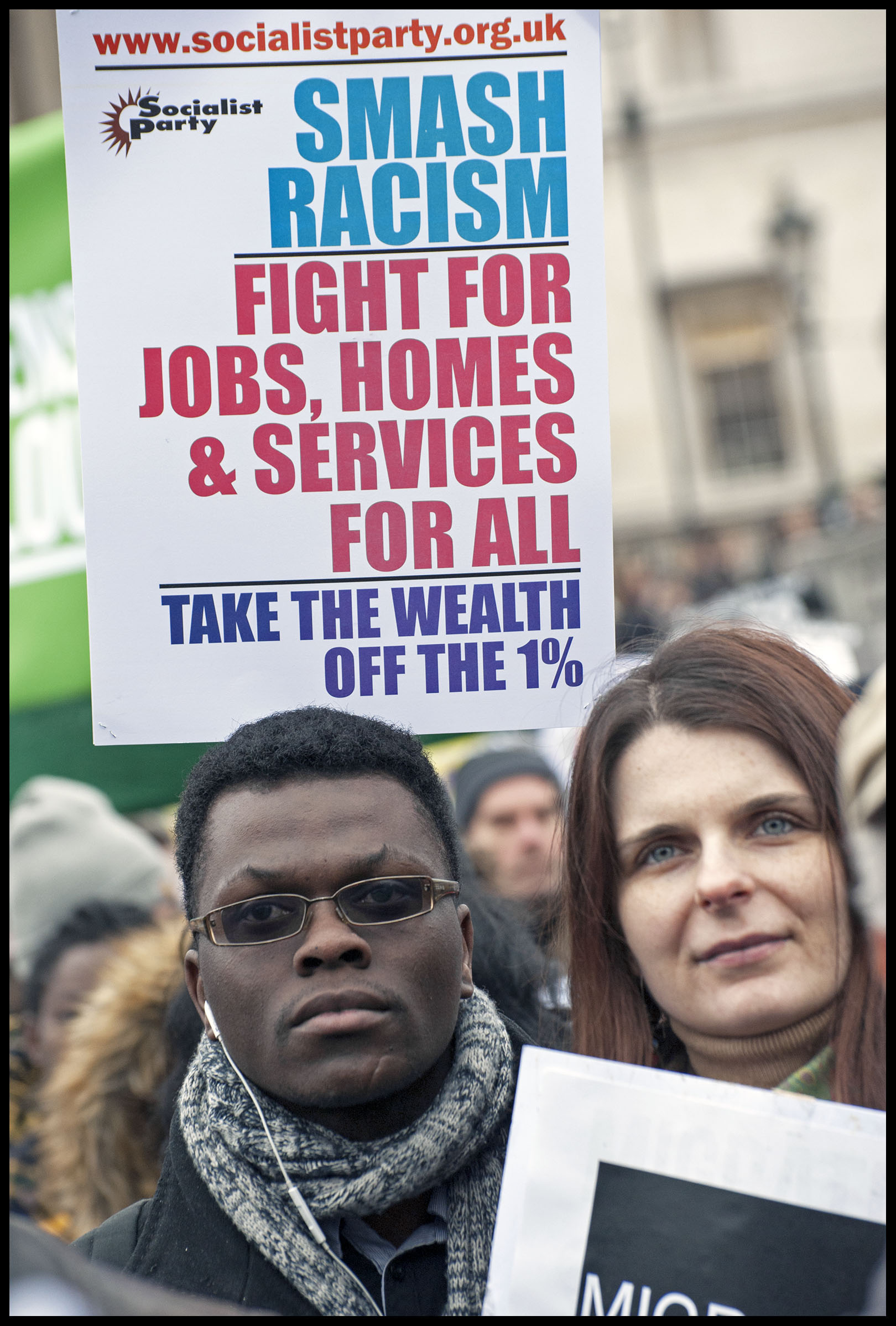

The far right still exists on both sides of the Atlantic and it must be fought. But as Militant commented after the 13 August counter-demo: “Ultimately the labour movement will be able to counter racism and fascism only if it is seen to be fighting to change the rotten conditions on which it spawns, by fighting for jobs, decent wages, more and better houses, better education and health services and for a socialist planned economy that would make these things possible for all.”

Four decades later, that is still true.