While the US, British and other western governments lick their wounds following their ignoble retreat from Afghanistan, after 20 failed years of ‘nation building’, another ‘failed state’, Libya, marks ten years since the West helped overthrow the Gadaffi dictatorship. Tom Baldwin examines the legacy of this imperialist intervention.

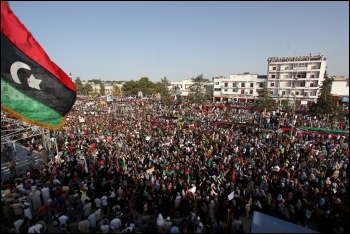

Muammar Gaddafi was deposed following a popular movement in 2011 that rose up against his rule, inspired by the revolutionary movements of the ‘Arab Spring’ which swept North Africa and the Middle East.

At the same time, Libya faced Western military intervention through Nato, and from other countries seeking to stamp their influence on the events unfolding in the region, and to further their own interests.

In the ten years that have followed, Libya has largely remained fractured and in a state of conflict. This has been primarily a struggle between two power blocs – backed by France, US, Britain, Russia and Turkey and others – which coalesced around rival governments based in the west and the east of the country.

However, throughout that time there has been a complicated and shifting patchwork quilt of control by different militias and tribal forces.

For the vast majority of Libyans, life has become a nightmare – facing militia violence and an absence of security, internal displacement, as well as widespread unemployment and a descent into poverty.

Oil production has been disrupted by power struggles and blockades, while oil revenues are fought over by the rival groupings and siphoned off by armed militias.

Desperate migrants and refugees seeking a route through Libya to Europe have been robbed, sold into slavery, or stuck in terrible transit camps. Some have been murdered. Those that manage to secure boat passage from people smugglers risk drowning in the Mediterranean Sea or being caught by European Union naval patrols and sent back to Libya.

There is currently a fragile ceasefire and attempts at political unification. The truce came about following the collapse of a 14-month long offensive by the eastern-based Libyan National Army, led by General Haftar, aimed at taking the western capital Tripoli.

There is a rocky road to travel between now and proposed elections on 24 December. The main difficulties are around attempting a reconciliation after years of conflict, and overcoming differences and distrust between different political and regional forces. However, even the practicalities of organising a poll will be a challenge in a country which still has well over 250,000 internally displaced people.

The framework for elections is supposed to be agreed by the 75-strong Libyan Political Dialogue Forum in talks mediated by United Nations officials. However, the last round of negotiations in Geneva were mired in acrimony and described as “out of control”.

None of these ‘delegates’ represent the working class and poor of Libya.

One of the stumbling blocks has been the continued intervention of international and regional powers, which have been pursuing the rival interests of their own ruling classes. Last year’s ceasefire agreement calls for the removal of such influence, but it still persists through the backing of local forces and the deployment of mercenaries and foreign troops.

This has been an issue for over a decade, since a military intervention led by Nato began in March 2011. The UK government joined the aerial and naval bombardment, with just 13 MPs voting to oppose. The intervention fulfilled a UN Security Council resolution and was ostensibly to protect civilians from Gaddafi regime.

Gaddafi had been in power since 1969 when he led the overthrow of the British-backed monarchy.

At times he claimed Libya was ‘socialist’, but it couldn’t accurately be described that way. The oil industry was nationalised and a redistribution of that wealth had considerably improved the lives of many in what had been one of the poorest countries in the world.

However, workers had no control over the running of society. Gaddafi wielded dictatorial power and enriched himself and his children. The oil industry began to be privatised in 2003. After that, the European powers’ had largely rehabilitated Gaddafi, and Libya became an important trade partner and oil supplier.

However, when the 2011 uprising began against him – inspired by the revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt, the so-called Arab Spring – Western imperialist powers turned against him again.

While Western airstrikes were supposed to be protecting Libyan civilians from Gaddafi’s armed forces, the imperialist powers were doing nothing about attacks on civilians in Bahrain and Yemen which their allies, including Saudi Arabia, were responsible for.

In reality, they were seeking to further their imperialist interests. They hoped to divert the flow of the Arab Spring and that it would lead to a new regime that was much more amenable to their interests.

No small consideration was the fact that Libya was the world’s 12th largest oil producer, sitting on Africa’s largest oil reserves.

Without an organisation with a clear revolutionary programme, around which workers and youth could organise their struggle, the movement against Gaddafi began to pull in different directions. Defectors from the old regime and pro-Western politicians began to try and push themselves into positions of leadership. Nato intervention further polarised the population and split the anti-Gaddafi forces.

Eventually, he was overthrown and killed but the revolution had been derailed, and the chance for workers and youth to take control of their destinies had been lost. The country fractured into areas controlled by opposing forces.

Like many colonies Libya was actually created by the colonial power, in this case Italy in 1934, amalgamating geographically separate regions which had their own tribal and clan identity and traditions. However, against a background of rising living standards, the sense of being Libyan strengthened during Gaddafi’s rule.

But in 2011 – in the absence of independent workers’ and popular organisations that could unite the working people and youth – Nato’s intervention, far from protecting civilians, laid the ground for a decade of chaos and conflict as the country split apart.

Barack Obama has described failing to prepare for post-Gaddafi Libya as the worst mistake of his presidency. But four successive presidents over 20 years also failed at ‘nation building’ following the western invasion and occupation of Afghanistan. These are just two countries on a long list where military intervention has ended in disaster for the local population.

The forces of imperialism will directly intervene only to pursue their own strategic interests. Their ‘support’ for the uprising was really an attempt to control and limit the Arab Spring.

Recognising this, revolutionaries in Benghazi had put up posters saying: “No to foreign intervention – Libyans can do it by themselves”.

Now we have the situation where the Turkish regime is trying to strengthen its position as a regional power by militarily backing the Tripoli based ‘government’, while the Russian state-approved Wagner mercenaries support General Haftar’s forces.

Only through self-organisation can workers and poor people take control of their own lives. This means building independent workers’ organisations and a party with a socialist programme – including calls for international solidarity – that can actually deliver on their aspirations.

What the CWI said in 2011

Shortly after Gaddafi’s killing, the Committee for a Workers’ International (CWI) wrote: “Now, more than ever, the creation of independent, democratic workers’ organisations, including a workers’ party, are vital, if working people, the oppressed and youth are to achieve a real revolutionary transformation of the country and thwart the imperialists’ plans, end dictatorship and transform the lives of the mass of the people. Without this other forces will step into the gap.”

Unfortunately, they did. But, although it will not be an easy task, a revival of a genuine mass movement, one that can unite working people in struggle, is still possible.

However, for lasting success, this would need to develop a programme that defends all democratic rights, is against oppression, and can organise democratic self-defence, involving minorities and migrant workers, against sectarian attacks.

The Committee for a Workers’ International (CWI) is the international socialist organisation which the Socialist Party is affiliated to. The CWI is organised in many countries. We work to unite the working class and oppressed peoples against capitalism, and to fight for a socialist world.