Militant Left (CWI members in Northern Ireland)

The results of the Northern Ireland Assembly election on 5 May mark a significant political turning point. For the first time since partition in 1921, a nationalist party has emerged with the greatest number of seats. The largest party in the Assembly holds the position of first minister, and the second largest party the position of deputy first minister. This means that Sinn Féin Vice-President Michelle O’Neill will become the First Minister in the new power-sharing executive when it is formed.

The positions of first and deputy first minister are co-equal in terms of powers, but Sinn Féin holding the first minister position is a hugely symbolic moment both for Catholics and Protestants. Most Catholics are in a celebratory mood while most Protestants are fearful for the future.

Every election in the North is treated as a mini-referendum on the constitutional future by the main parties and the media. The outcome of this election is undoubtedly a watershed moment, but it is important to register not just what has changed, but what has not changed. Sinn Féin has emerged triumphant, but its share of the vote only edged up by 1% – from 28% to 29% – and it returned with exactly the same number of members of the legislative assembly (MLAs) as before: 27.

It took pole position because of a significant fall in the vote of the major unionist or Protestant-supported party, the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP). The DUP dropped from 29% to 23.7%. As a result it lost four seats, and now has 25. The DUP lost votes to the more moderate Ulster Unionist Party (UUP), but many more to the hardline Traditional Unionist Voice (TUV).

It also lost the votes of many working-class Protestants who could not stomach voting for a party which has delivered nothing on the economic and social issues.

The biggest winners in the election were the Alliance Party, which seeks to win votes from both Protestants and Catholics. In 2003, it won under 4% of the vote, but it gained 13.5% this time around, and more than doubled its number of seats. Traditionally, Alliance attracted an older and more middle-class vote, but this is clearly changing. Its right-wing economic policies (it is in favour of lowering taxes on big business and imposing water charges, for example) do not appeal to disillusioned young people seeking an alternative.

The trebling of its vote over the last 20 years is accounted for by several factors. It has taken votes from both the more moderate wing of unionism, represented by the UUP, and the more moderate wing of nationalism, represented by the SDLP. In some constituencies, Alliance will be seen by these voters as a better option than allowing a hardline party from the ‘other community’ to win the seat. It is not just that Alliance provides a home for softer nationalists and unionists, however. It is now seen as the most credible alternative to the main sectarian parties for those who are sick of the politics of division. It took votes from the Green Party on this basis and, as a result, both Green Party MLAs lost their seats.

It is important to note that while Sinn Féin emerged as the largest party, the votes cast for all unionist parties remain ahead of the votes cast for all nationalist parties. The total nationalist vote was almost identical to the last election in 2017, at about 41%.

The unionist vote did go down, from 45% in 2017 to 43% of the vote, but it remains just ahead in both percentage terms and in the number of seats (37 v 36). As a result, the balance of forces has not tilted decisively, and Sinn Féin’s demand for a border poll within five years will not gain enough momentum to force Boris Johnson’s hand at this point. Nevertheless, Sinn Féin and other nationalists will raise the issue more than ever in the period ahead, and this will destabilise the situation even further.

The third winner in the election was the TUV which, while it did not increase its seat tally (one only) it gained 7.5% of the total vote. One in six unionist voters now support its hardline positions on the Northern Ireland Protocol. Its vote is a clear indicator of the mood in Protestant areas and the dangers that lie ahead.

The TUV is closely linked to the forces which have mobilised for a series of anti-Protocol rallies over the last year. Alongside it on the platforms have stood a new generation of young loyalists who have the ear of a layer of young Protestants, both in rural and urban areas. The rallies have referenced historical events from the past when unionism armed and resisted by force or the threat of force.

The TUV vote will act as a check on the DUP if it tries to go into the executive with only minimal or cosmetic changes on the Northern Ireland Protocol. The DUP are seeking at least significant changes in the Protocol before they will consider going into government. The Protocol results in checks on goods passing from England, Scotland or Wales to Northern Ireland. This has resulted in delays and some localised shortages but the real problem for Protestants is symbolic as it creates a new border in the Irish Sea. If Brexit had resulted in a similar hardening of the North-South border, there would also be turmoil and Sinn Féin would have collapsed the institutions.

In the short term, it is unlikely that a new executive will be formed. Boris Johnson is threatening to unilaterally set aside the Protocol. There may be a sudden development in the coming days, but it is also possible that negotiations will continue for months. Whatever happens next, the North will remain in a state of crisis. Previously, an executive had to be formed within eight days after an election and, if it was not, a new election would be called.

The period for negotiations has now been extended to six months. In the meantime, the law allows a shadow Assembly to meet and monitor shadow ministers who continue to exercise their functions, but this arrangement has now been thrown into crisis as the DUP has refused to nominate a speaker for the Assembly.

Politics will stumble on against a background of fractious negotiations, with the danger of Protestant anger being expressed on the streets in demonstrations. These could become larger and possibly result in street violence, as seen in the rioting last spring and summer. Catholics, even those who did not vote for Sinn Féin, will be angered by the delay. It will appear to them that the DUP is determined to block the appointment of Michelle O’Neill as first minister.

Class issues like the cost-of-living crisis and housing were very prominent in the election campaign. Politicians from all parties felt obliged to reflect this in their material and in their media appearances. Much hot air was generated as politicians fell over themselves to promise the earth. These are the same politicians who delivered nothing over the last five years and most voters know they will deliver nothing on these issues over the next five if an executive is ever put back into place.

These are the contradictions of Northern Ireland politics. On a day-to-day basis Catholic and Protestant workers unite in their workplaces, and in community campaigns, in struggles together for a better future. Simultaneously, workers are divided on issues relating to identity and nationality. In this election, the divisive issues were dominant and ultimately determined the result of the election. The fact that one-third of voters did not vote at all, and that one and six of those who did voted for anti-sectarian parties is, however, significant.

Many of these are clearly turned off by the sectarian nature of politics and would be open to a political alternative that was both anti-sectarian and addressed the issues of low pay, job insecurity and weakened public services. If a credible anti-sectarian and cross-community party of the working class begins to develop, there is a large potential base to be won over.

Cross-Community Labour

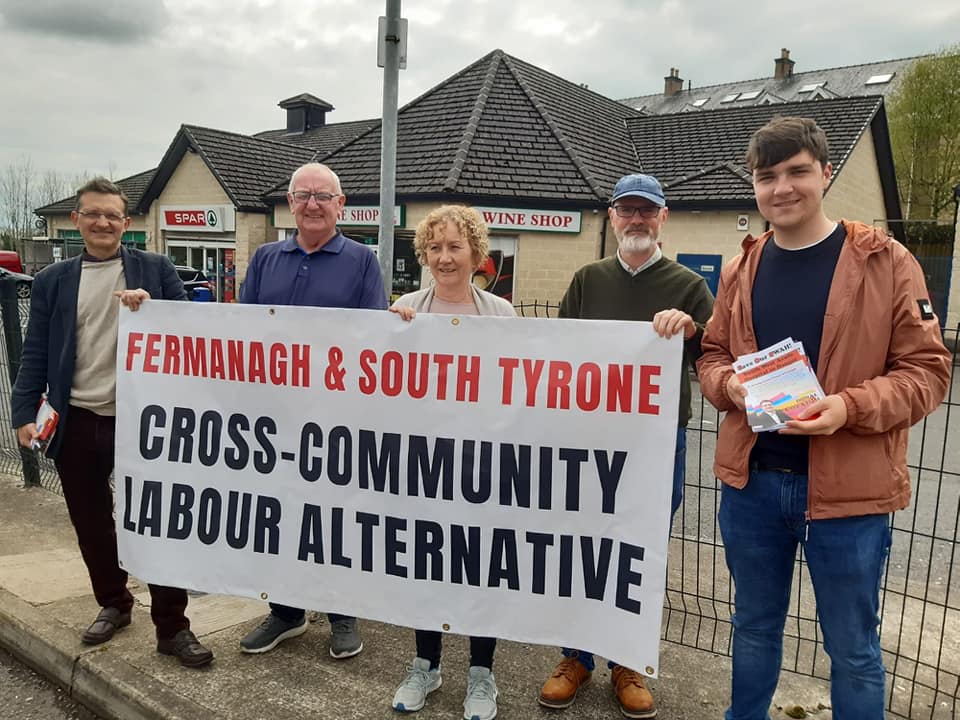

Councillor Donal O’Cofaigh stood in the Assembly election for the constituency of Fermanagh and South Tyrone. Donal was elected as a councillor in May 2019, and since then has established a high profile as a fighter for ordinary people. He stood as a candidate for Cross-Community Labour Alternative.

This is a broad coalition in Fermanagh and South Tyrone, including activists who previously belonged to the British Labour Party during the years when Corbyn was leader, a group of activists in Dungannon who work with former councillor Gerry Cullen, and activists from the Committee for a Workers’ International tradition, including members of Militant Left, to which Donal belongs.

The campaign was focused on class issues and gained a real echo. Two newsletters were distributed in all the major working-class areas, and a manifesto went into every home in the constituency. Despite the small team involved, most of the constituency was canvassed. The campaign was a success in that a clear socialist alternative was articulated and brought to the doorsteps across the constituency.

Donal won 602 votes which is a credible achievement given the circumstances. The vote achieved was a modest success given the huge pressures in what was a tense, high-stakes election. Fermanagh and South Tyrone saw one of the highest turnouts of any constituency as a reflection of sectarian polarisation, and it also saw the lowest total votes for anti-sectarian parties. There is little doubt that some voters who were looking to Donal returned to either sectarian camp in the privacy of the ballot box because of the pressures in wider society.

Donal lost votes to the Alliance Party which stood a candidate who did not live in the area, and ran a very limited campaign, but who still won 2,500 votes, carried along on the ‘Alliance surge’, which saw it increase its vote in all areas. Other potential supporters simply stayed a home as they did not believe that Donal could win.

All forces who are broadly ‘on the left’ suffered setbacks in the election across the North. The Green Party lost 20% of its vote and both its seats. People Before Profit, which stood on a left-nationalist platform, lost votes for the second Assembly election in a row. It managed to defend its single seat in West Belfast, but it has lost 40% of its vote since 2016, even though it stood in twice as many seats.

Donal’s campaign team is looking to the future and considering how to approach the next local elections in 2023. The priority must be to defend Donal’s seat, and nothing can be taken for granted. The possibility of standing other candidates across Fermanagh and South Tyrone is being considered. A slate of candidates, from both Protestant and Catholic backgrounds, standing together on class issues, would send a very powerful message.

Cross-Community Labour was established in 2016 as a vehicle for those who believe that a mass left alternative can, and should, be built. It has stood candidates in several constituencies since 2016, but in this election Donal was the only candidate. It is possible that it will stand more candidates in next year’s elections outside Fermanagh and South Tyrone, and wide-ranging discussions with others about this possibility are now essential.

Cross-Community Labour represents an idea: that Catholic and Protestant workers and young people have more in common than divides them, and a political united voice is necessary if we are to win a better life for all, and overcome the divisions in the working class. Only class politics offers a way forward. Each election presents an opportunity to build support for this idea. Donal’s stand on 5 May was another small step in the direction of independent working-class representation. Defending Donal’s seat in next year’s council elections, possibly alongside a slate of other candidates, is the next.