Paul Callanan, Socialist Party national committee

The surge in support for Corbyn’s radical programme at last year’s general election and the collapse of Carillion has led to a widespread discussion around public ownership and nationalisation. Polls show widespread support for the renationalisation of railways, gas, electricity, water, the Royal Mail and the NHS.

Is it any wonder that in the minds of workers and young people the question of falling living standards and growing inequality is going hand in hand with a questioning of who is really in control in society. By 2030 on current projections, 1% of the population will own 64% of all wealth. The richest 1,000 bosses are now worth £724 billion and have seen their wealth increase by 10% in the last year.

Meanwhile, working class people in Britain have endured the longest fall in living standards since records began. And across the world nearly half of humanity lives off less than $2.50 a day. 80% of all people live in countries where wealth differentials are growing.

Essential policy

The concentration of wealth and power in an ever-vanishingly smaller number of hands is linked to the growing immiseration, insecurity and precariousness for the majority.

The question of how we take control from the hands of the bosses and provide solutions to the problems faced by working class and poor people is therefore an extremely important debate for all those engaged in struggle for socialist change.

For socialists, nationalisation under democratic workers’ control and management is a key means through which power can be taken out of the hands of the bosses and placed in the hands of working class people. Genuine socialists don’t only fight for improvements under capitalism, we seek to get rid of it altogether, along with the crisis, inequality and chaos that comes with it.

That is not to say we don’t fight for reforms. We are at the forefront of all workers’ struggles for a £10 an hour minimum wage, free education, an end to NHS cuts and so on. But as the saying goes ‘you can’t control what you don’t own’. Any victory won or gain made is important. However, while overall control of the economy remains in the hands of the capitalist class, there is a danger that any reform won can be reversed.

Socialists have always defended the original Clause IV, Part 4 of the Labour Party constitution (see below).

It was this passage that committed the Labour Party to the historic goal of public ownership of the commanding heights of the economy. It was adopted by the party in 1918 in wake of the Russian Revolution. The pro-capitalist leadership of the party saw this as a concession they had to grant in order to prevent haemorrhaging support to the new workers’ state and the idea of fundamental change.

For the mass of workers in the Labour Party, however, it was seen as Labour’s commitment to socialism and as a tool with which to force the party to adopt reforms favourable to the working class.

Support for nationalisation was demonstrated in 1972, when a motion moved by Militant supporters (forerunner of the Socialist Party) calling for an enabling act to nationalise the top 350 monopolies was passed at Labour Party conference. At that stage the top 350 companies represented around 80% of the economy – ‘the commanding heights’. Nationalisation of these companies, under democratic workers’ control and management, could have represented a break with capitalism and laid the basis for the development of a democratic socialist plan of production.

All through the party’s history there were attempts to get rid of Clause IV. Various right-wing and reformist leaderships saw this as part of freeing themselves from any pressure to deliver socialist change.

Hugh Gaitskill, Labour leader from 1955-63 was defeated in his attempt to remove Labour’s socialist pledge. It was only on the basis of the defeat of the miners’ strike, the collapse of Stalinism and the resultant throwing back of class consciousness, that Tony Blair was able to end Labour’s historic commitment to socialism.

The clause adopted by the party as part of the Blairite counterrevolution committed the party to the dynamic “enterprise of the market”, “the rigor of competition”, and “a thriving private sector”. It was designed to reassure the ruling class that a future Labour government would pose no threat to them whatsoever.

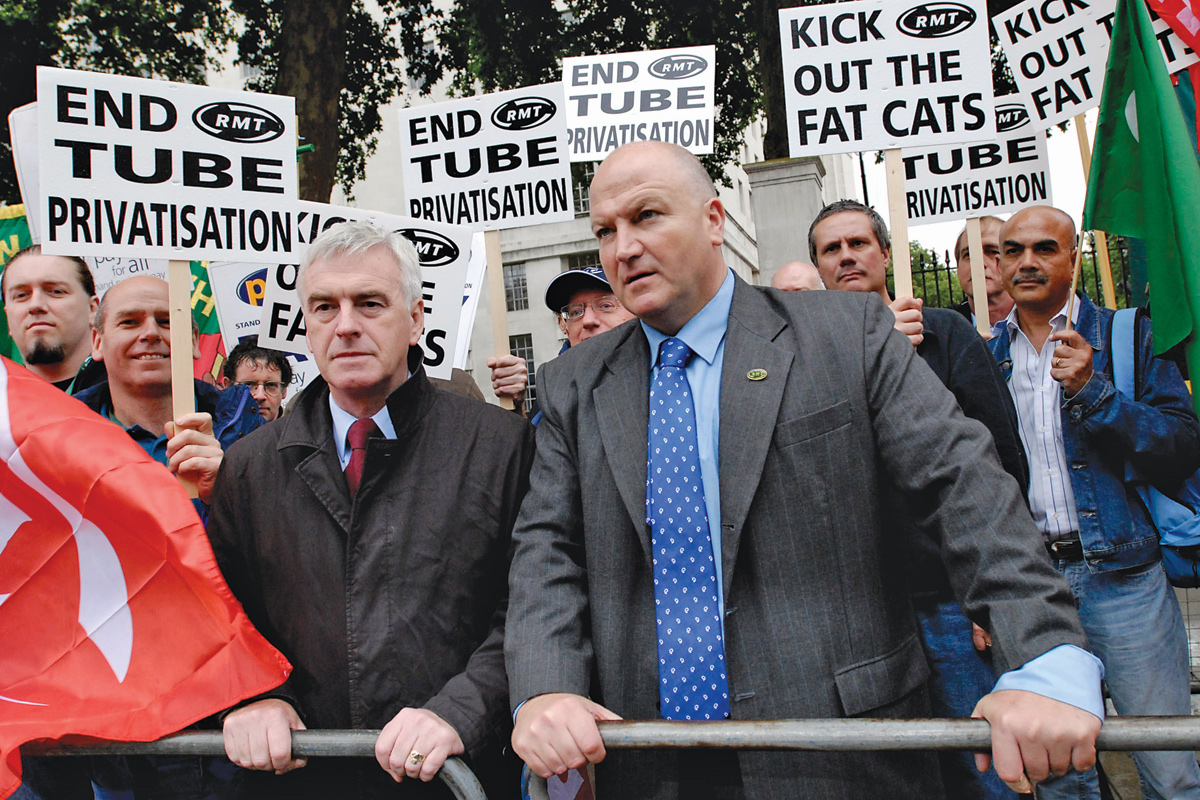

Under Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell’s leadership of the Labour Party there have once again been important steps forward towards supporting nationalisation.

In the wake of Carillion’s collapse this January, Shadow Chancellor John McDonnell said the next Labour government would commit to “taking them back” in relation to privatised public services and the energy and utility companies. However, an examination of the detail of the Labour leadership’s programme in relation to public ownership reveals that’s not quite the case.

In their recent report ‘Alternative Models of Ownership’ the Labour leadership outline a number of measures on public ownership. They envisage a mixture of government-owned public services and regionally and municipally owned energy and water companies.

At the launch of the report Corbyn said: “We need to take a new direction with a genuinely mixed economy fit for the 21st century that meets the demands of cutting edge technological change”.

For Corbyn and McDonnell nationalisation is not a measure for transforming society. They instead wish to change the existing one, ameliorating the worst effects of capitalism on working class people. McDonnell has spoken since becoming chancellor about “transforming capitalism” or even “stabilising capitalism”.

The dangers of this approach are manifold. Take for example the energy sector. At present the ‘big six’ corporations in this sector control 80% of the market. This would leave small public local and regional enterprises scrambling around for a small share of the market.

They would still be vulnerable to market forces, with the big companies – on the basis of huge profits and greater access to the national grid – much more able to lower prices. It certainly could not be ruled out that they would become locked in unwinnable price wars with each other and the big six.

The banks would be far less willing to invest in small council or regional public companies and cooperatives. Firstly, because the big six are a better guarantee of a return on their investment. There would also be an unwillingness from capitalists to invest in enterprises that are seen as a threat to their control.

We support Corbyn and McDonnell’s plan to fully renationalise the NHS, but it needs to go further. The NHS is in thrall to big pharmaceutical companies.

In 2017 alone the NHS paid £31 billion to greedy companies for drugs that treat illnesses like cancer, MS and arthritis. Hikes in prices of drugs like Tomoxifen and Bulsufan, which treat cancer, mean that they have to be rationed. The nationalisation of the pharmaceutical companies is key to ensure the future of the NHS.

Ruling class sabotage

A Corbyn-led Labour government would give the working class confidence and an appetite to fight for more. Such a government would instantly be opposed by the forces of the ruling class. They will use every means at their disposal to undermine and defeat Corbyn’s attempts to implement a programme of public ownership – no matter how limited. This would include use of the media, the state and economic sabotage.

The Macquarie Group, an investment bank with interests in UK utilities, has already advised investors to start moving businesses and assets abroad in order to protect them from any future nationalisation.

This is just a very small glimpse of the kind of economic measures the ruling class would use in the event of a Corbyn government. This raises the need to nationalise the banks which are responsible for 12-15% of all UK investment.

Only by nationalising the commanding heights of the economy, today around 125 massive corporations and banks, would it be possible to break the power of the capitalist class and lay the basis for building a society that really met the needs of ‘the many not the few’. Compensation should not be paid to the fat cats, but only to those small shareholders who are genuinely in need.

Even Labour’s programme of nationalisation implemented in the aftermath of World War Two, which went much further than Corbyn’s current proposals, fell prey to capitalist sabotage.

With the collapse of the economy after the war and the threat of revolution which was sweeping Europe, the ruling class felt that they had no option but to make big concessions to the working class. This included the welfare state, the creation of the NHS and the taking of big sections of the economy into public hands. Coal, the utilities, and many other industries were nationalised.

However, they were set up to fail from the start. Rather than nationalised on the basis of democratic workers’ control and management, they were run by bureaucrats from Whitehall. In some cases, such as in the coal industry, the old bosses who had run them into the ground were put onto the new boards. Without the input of workers and the people who relied on those industries, starved of investment and run on a capitalist model, there were inevitably inefficiencies.

Thatcherism

The economic crisis that began in the mid-1970s was blamed on nationalised industry and used as excuse to begin reversing the gains of the post-war period. Thatcher declared war on the working class and embarked on a vicious privatisation programme. The programmes of successive Labour and Tory governments since have been continuations of this process.

Along with the nationalisation of the companies that control the wealth and resources of society, the question of democratic control is key. Socialist nationalisation would include having elected committees to run every workplace. In turn these would elect representatives to be on committees that would form regional and national government. On this basis the whole of society would be able to take part in drawing up a plan for what industry should produce.

A socialist plan, with workers free from exploitation and oppression, could unleash the full productive and creative potential of humanity. And on that basis we could eliminate poverty and inequality.

The Constitution of the Labour Party Clause IV (4)

To secure for the workers by hand or by brain the full fruits of their industry and the most equitable distribution thereof that may be possible, upon the basis of the common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange, and the best obtainable system of popular administration and control of each industry or service.

- Clause 4 was adopted in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution and seen as Labour’s commitment to socialism. It was jettisoned by Tony Blair’s New Labour