P Daryaban, Committee for a Workers’ International (CWI)

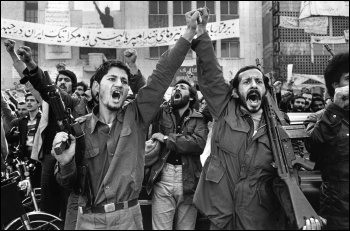

Forty years ago a great revolution against a dictatorial monarchy was in progress in Iran. Recalling those days still inspires us: scenes of comradeship despite the shortages due to long days of nationwide strikes, initiatives by ordinary people to run their communities and workplaces, mass demonstrations, resistance to sometimes brutal repression and the pinnacle of those events – an armed insurrection that overthrew the old regime of the Shah.

However, the revolution did not end up as socialists expected. Like many other revolutions, counter-revolution rose amid blood and fire.

The subsequent seizure of power by the most reactionary section of Iranian society has provided pro-capitalist reformists, monarchists, liberals and so on, with an excuse to condemn not only Iran’s 1979 revolution but also to deny the necessity of revolutionary change.

Despite this falsehood, we must mark that revolution and learn from its complicated processes and ultimate defeat.

Dynasty

Iran’s modern history is characterised with two great events. First, the 1905-1911 ‘Constitutional Revolution’ which aimed to put an end to the feudal rule of the Qajar dynasty.

After about two decades of political turmoil, the Pahlavi dynasty, which had succeeded the Qajar, destroyed the gains of the revolution and erected an imperialist-backed dictatorship.

World War Two led to the then newly allied Britain and the Soviet Union moving to remove Reza Shah Pahlavi in August 1941. This was because they saw him as trying to balance between them and Nazi Germany.

In his place his son, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, was declared Shah (King). These events opened up a new phase in Iranian history as workers’ and popular movements developed.

This new period saw a movement for the nationalisation of the oil industry, which was then controlled by British imperialism. But a US-UK backed coup in 1953 put an end to this movement and opened the way for the new Shah to impose authoritarian rule.

This defeat was mostly due to the weakness of the National Front led by capitalist-nationalist prime minister Mohammad Mosadeq and the inaction and cowardice of the Tudeh Party’s leadership, formed in the 1940s as the successor to the Iranian Communist Party.

The Tudeh Party leadership’s full submission to the Stalinist Soviet Union increasingly weakened its appeal.

At the same time, as a result of its programme of allying with what it saw as the ‘progressive capitalists’ as the next step in developing Iran, it failed to use its mass influence to independently mobilise the working class and poor around a revolutionary socialist programme, and thereby failed to take advantage of that historic chance.

In the years following the 1953 coup, along with excessive repression, the Shah’s regime earned huge revenues due to a rise in oil prices. Under US auspices, the regime carried out a land reform, which accelerated an imperialist-dominated capitalist development.

The Shah, who embodied the feudal class, now represented the ‘comprador bourgeoisie’ (local capitalist class acting as a client of imperialism).

The emergence, from the early 1960s, of elements of a more modern bourgeois-imperialist system led to the bankruptcy of the traditional middle classes as well as organisations of the Shia Muslim clergy.

Frictions

This increased friction between the regime and sections of the clergy, like those around Khomeini – although the regime continued to be on good terms with senior clerics who always served as a barrier to the left and revolution.

Through petrodollars, Iran’s GNP (total output plus overseas earnings) growth rate reached about 30% in 1973.

Despite the improvement in living standards for some people, an unprecedented class differentiation developed. A wealthy 20% consumed more than 50% of total goods and services in the mid-1970s.

However, the Shah’s ambitious plan to modernise the country with the support of imperialist powers (which had assigned him the role of ‘policeman’ of the Middle East) ended up in a crisis.

The decay of traditional agriculture in the interests of the service sector, and industry to lesser extent, caused a huge migration of the peasantry to the cities. These members of the impoverished peasantry resided as seasonal unskilled workers in slums around large cities.

Months before the beginning of political demonstrations, these people engaged in clashes with gendarmes and municipality officers who tried to destroy their dwellings.

Anger

A large portion of the oil revenues went into services and unproductive activities rather than industries. Furthermore, capitalist development in Iran was highly oil-driven. So a shock in the oil market caused a sharp fall in economic growth.

The economic downturn and the unprecedented gap between the poor and the rich ignited the masses’ wrath, but this was only a part of the story. The people viewed the Shah as a puppet of imperialism and believed that the US was plundering Iran with the aid of the regime.

Against this background the revolution started in 1977 with sporadic demonstrations. In 1978, hundreds of people were killed in clashes with the police. The declaration of martial law in large cities did not silence the masses.

General strikes paralysed the regime. More than 100,000 oil industry workers inflicted the heaviest blow on the moribund regime by a strike which cut off Iran’s oil exports.

Faced with mounting, determined opposition and amid signs of fissures in the state machine, especially the conscript army, the weakening Shah fled the country in early 1979. The revolution reached its pinnacle in February with a two-day armed insurrection that put an end to the monarchy.

In the last weeks of the monarchy the militancy of the masses grew. This alarmed both imperialism and Khomeini. People demanded: ‘Leaders! Arm us!’ But, Khomeini’s aides were in covert negotiations with US officials and the army generals. Just a few days before the armed insurrection, Khomeini said he had not ordered a jihad (holy war) and desired a peaceful transfer of power.

Western imperialist countries, which were no longer able to keep the Shah in power, preferred a compromise and the formation of a government composed of Khomeini and his followers, as well as the remnants of the monarchy, especially the army.

However, the tempo of events in a revolutionary situation was so high that nobody could either predict or prevent people’s moves. On 10 and 11 February 1979, clashes between pro-revolution junior officers and monarchists in a barracks ignited the armed insurrection.

The Fadayeen left organisation held a large demonstration a day before in Tehran University that enabled it to organise its supporters rapidly to engage in the insurrection, capturing radio, TV and police stations. However, because many Iranians had illusions in Khomeini, the ultimate winner was him not the left.

The two-day armed uprising had huge impacts on the military and bureaucratic machine of the former regime and paralysed it. In the vacuum created by the insurrection, Khomeini and capitalist factions started to modify the old machine in their own interests.

Alongside the weakened state, revolutionary organs – councils and committees – mushroomed all over the country and ‘dual power’ emerged.

Power and purges

Khomeini and his clique initially had to move carefully to curtail and then crush the revolution. Two years after the revolution, the new regime began crushing it, using false slogans that they were ‘protecting the revolution’.

A wave of executions and arrests of political activists, dissolution of people’s councils and committees, and the imposition of a regime of terror, left almost nothing of the revolution’s gains by the mid-1980s.

The Iran-Iraq war (1980-1988) also helped Khomeini to more brutally crush opposition under the false banner of national unity and defending the revolution.

Based on the dominant ‘anti-imperialist’ discourse of those years, many on the left were disoriented when Khomeini’s regime continued its confrontation with the Western powers, despite an expectation that it would soon turn into an ally of imperialism.

This confusion caused a major part of the revolutionary left in the Fadayeen organisation to join the Tudeh Party. The Tudeh had supported the Islamic regime from the beginning and shamelessly cheered the repression of the opposition, until it too was brutally crushed in 1982-83.

This policy led to sacrificing the immediate demands of the working class for illusory “non-capitalist development” under Khomeini’s reactionary regime and, ultimately, to collaboration around 1981 with the regime’s purge.

The Iranian revolution taught a historic lesson: that socialists cannot select their allies on the basis of ‘my enemy’s enemy is my friend’. The rise of the reactionary political Islam in recent decades is a proof of this.

As the experience of the Bolshevik revolution in October 1917 showed, only a clear policy based on correct understanding of the concrete development of the revolution, explaining and winning support for a clear programme, and emphasis on the political independence of the working class from pro-capitalist forces, can guarantee the victory of the working class.

Based on its faulty understanding of the situation, the ‘revolutionary’ left – which expected a new revolutionary wave to rise – failed to secure an organised retreat after the Islamic regime started its huge crackdown in 1981, leaving rank-and-file members vulnerable to brutal repression.

New revolutionary wave

Forty years later, a new revolutionary tide is rising in Iran. Iranian workers have been in the lead of the protests that started in November 2017. Significantly many of the demands that have arisen are not just economic and social but

political – including the right to form independent workers’ organisations, for re-nationalisation of privatised companies and for some form of workers’ control.

Under the repressive theocratic regime, workers are battling to form their own organisations for economic and political activities. But as in 1979, there also exist forces with the potential to hijack this new revolutionary wave – pro-imperialist monarchists, liberals, reformists, bourgeois nationalists and so on.

Under these critical circumstances we must learn the lessons of the 1979 revolution. This means adhering to a revolutionary socialist strategy. It means moving to build independent workers’ organisations, including a mass party that can clarify the steps needed to achieve the real transformation of Iran.

- Full article on socialistworld.net

Forces in the 1979 revolution

- Khomeini and the clerical organisation that supported him. Khomeini was almost unknown until a few months before the revolution but had an influence on the middle and upper-layers of the traditional petty-bourgeoisie (merchants, rich farmers, etc), and had developed links with the bazaar.

- Previously, the regime’s incessant campaign against the left, for which it found religion a good tool, provided the mullahs with an opportunity to expand their networks.

- Iranian middle bourgeoisie organised in nationalist and liberal-religious parties such as the National Front and the Freedom Movement. In many ways the left reformism embodied in the Tudeh Party (formerly the Iranian Communist Party) could be classified under this category.

- The revolutionary left was largely represented by two urban guerrilla parties, Fadayeen and Mojahedin (originally a radical petty-bourgeois party with a Marxist interpretation of Islam, whose majority subscribed to Marxism in 1975). These parties had a great influence mainly among university students and intellectuals. As they emerged from their clandestine activity and approached the masses they won a considerable support among workers, teachers, women and young people.

Solidarity with Iranian workers today

The current Iranian regime has re-arrested Esmail Bakhshi, the representative of the Haft-Tapeh sugar cane agro-industry workers, and activist Sepideh Qolian.

The Haft-Tapeh workers have frequently suffered delays and non-payment of their wages since the privatisation of the factory and on 5 November 2018 they went on strike.

Security forces arrested Esmail Bakhshi and Sepideh Qolian. Under mounting public pressure, including international condemnation, and the continuation of workers’ protests, the regime freed them after one month’s detention.

In early January Bakhshi and Qolian spoke out on their torture in prison. On 21 January, the regime arrested Bakhshi and Qolian again. We are unaware of their situation in prison since then.

- Full report on socialistworld.net