Editorial of the Socialist, issue 1170

The Birmingham Erdington by-election showed, with a pitiful turnout of just 27%, that the task of building a new vehicle for working class political representation following the defeat of Corbynism within the Labour Party will not be an easy or straightforward one.

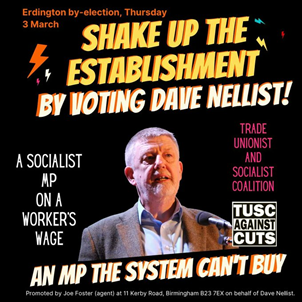

The Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition (TUSC), whose candidate in Erdington was the Socialist Party member and former Militant Labour Coventry MP Dave Nellist, took third place on 3 March.

The actual vote was undeniably modest – 360 (2.1%) – and well behind Labour and the Tories. But it put TUSC ahead of the Liberal Democrats, the Green Party, the Brexit Party (now renamed as Reform UK) and six other contenders.

Under a heading playing on the weather conditions during the rushed-through campaign, ‘Labour survives four storms and a local earthquake – but there’s a little tremor from the left’, the Sky News chief political correspondent, Jon Craig, wrote that TUSC’s third place showing was still “a performance that will cheer up all veteran left-wing comrades and Starmer critics”.

But the most important takeaway from this by-election – held against the backdrop of a two-year global pandemic and a war in Ukraine, and as the revival of Blairism in Keir Starmer’s Labour makes the different faces of the capitalist political establishment essentially indistinguishable – is the evidence that Erdington provides of the profound alienation and angry disengagement from ‘politics’ of broad layers of the working class, in Birmingham and nationally.

And that TUSC, despite being well-received amongst the small segment of the population it was able to reach in its campaign, did not have the authority or weight at this stage to become a mass outlet for the underlying rage.

Alienation

Out of the 62,996 registered electors in Erdington – and there were thousands not registered after the changes made by the 2010-15 Con-Dem coalition government – just 17,016 people voted: the 27% turnout was the tenth lowest in a by-election since 1945, not counting the Southend West and 2016 Batley and Spen polls which were effectively uncontested after the assassinations of the sitting MPs.

Labour’s highest vote in Erdington since 1997 was the 21,571 it polled in 2017, as part of the national ‘Corbyn wave’ in that election in response to the anti-austerity message symbolised in his leadership. This time, with Starmer determined to distance himself from ‘Corbynism’ and its radical reformist policies at all costs, Labour polled 9,413 votes – down 8,307 even on its 2019 general election score – but still enough to defeat the Tories, who also lost almost eight thousand votes.

Reform, who had come third in Erdington in 2019 on the back of the Brexit Party winning the national vote in the European parliament elections that year, lost over a thousand votes, finishing behind TUSC. The Liberal Democrats, just seven years ago a ‘party of government’ and still with councillors in a ward that neighboured Erdington, were even further behind.

And yet the BBC excluded TUSC from its pre-election hustings radio show, defending what it admitted was its ‘editorial discretion’ to do so or not, on, of course, purely ‘objective’ grounds. Once again TUSC can say that it polled better than the share of establishment media coverage it received.

An unfilled vacuum

The capitalists’ political representatives really do have a weak social base to lean on. But they will need to lean on it heavily in order to impose the massive post-Covid austerity attacks they are planning on workers’ living standards and public services in the period ahead. None of the capitalist parties any longer have deep social roots. This will be a problem they face not just in Erdington but in every corner of Britain too.

But it is also true that alienation and disgust expressed through electoral abstentionism will not solve the problems that the working class face. Indeed, aside from the exceptional circumstances of an organised mass boycott of ‘politics’ in favour of an alternative power, it is actually also a form of individual acquiescence to what ‘those up there’ seek to impose, not a collective response.

The working class needs its own party, to bring together its different discontents and concerns – and above all, its different struggles – to point a way forward and develop an encompassing governmental alternative. Without organisation, in unions but also in a mass workers’ party, we can only face up to all the consequences of the capitalists’ control of society as individuals not as a class.

Helping to build a new workers’ party is, the Socialist Party believes, the key task that TUSC must continue to pursue, and the key message from Erdington. The third place won was an important step, and needs to be followed up with a drive for candidates to stand in the May local elections and a renewed campaign in the trade unions.

But it won’t settle the debate on how to fill the gaping vacuum that exists and the Socialist Party will continue to patiently argue for the steps the workers’ movement needs to take to find its political voice.

Workers’ representatives on a worker’s wage

The by-election campaign began amidst talk of a no-confidence vote in Boris Johnson by Tory MPs as the ‘partygate’ scandal fed the widescale disgust at the capitalist establishment politicians, all seen as being in it for themselves.

Dave Nellist’s record as a workers’ MP on a worker’s wage, only taking the wage of a skilled worker in his nine years in parliament from 1983-1992, was an obvious counterpoint.

But even on this simple issue of fact the BBC was subtly misleading, if not deliberately confusing the position. In their obligatory mention of Dave in the list of candidates standing in Erdington, they wrote that “during his time as a Labour MP, Mr Nellist said he donated most of his salary to charitable and political causes”. Not that he did – irrefutably, with documented evidence, and not to ‘charity’ but to workers and community campaigners in struggle – but that he “said”, making Dave out as an individual do-gooder acting on a personal whim, not an accountable representative of Coventry workers.

In fact, Dave’s parliamentary accounts, including his wage calculated from figures compiled across ten Coventry factories by the AUEW engineering workers’ union (now part of Unite), were presented annually to the Coventry South East Constituency Labour Party general management committee (GMC), composed of trade union and local ward party delegates, and open to those delegates’ inspection.

If he hadn’t stuck to his pledge he would have faced the possibility of deselection by the GMC. But with the long ago transformation of the Labour Party from a workers’ organisation into Tony Blair’s capitalist New Labour – GMCs lost their power to select candidates in 1993, even before the abolition of Labour’s socialist Clause Four in 1995 – it is no surprise that there is limited understanding of what it means to be a workers’ MP on a worker’s wage. Jeremy Corbyn’s biggest mistake was not to use his leadership to spearhead the retransformation of the Labour Party into a democratic mass working-class party.

Nevertheless, if the 1 March announcement that MPs would get a £2,200 rise to bring their bloated pay up to £84,144 in April had not been swamped by the coverage of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, launched as polling day approached, the echo for Dave’s stand as a workers’ MP in Erdington may well have been even bigger.

Most importantly, the principle of workers’ representatives living on workers’ wages as a means of keeping them in check has been revived for a new generation.

TUSC and the Workers Party

The first post-Erdington meeting of the TUSC all-Britain steering committee will be considering a proposal to give observer status to the Workers’ Party of Britain, led by the former Labour and then Respect MP George Galloway.

The Workers Party is not just George Galloway, having senior level supporters for example in the other two railway worker unions, ASLEF and TSSA. But neither should its strength be exaggerated. It has reported 4,500 members but only an annual membership income of £21,000: at £4.70 a head per year, less than the political levy paid as part of their £280 annual union subs by RMT members.

Electorally, its 25 council candidates in May 2021 polled at the same level as the 272 council candidates standing under the TUSC umbrella. And while George Galloway, of course, has twice been elected to parliament in opposition to New Labour – in Bethnal Green and Bow in 2005 and Bradford West in 2012 – he has also polled more modest votes, 1.4% in West Bromwich East in 2019, 1.4% for London mayor in 2016, and 1.5% in the South Scotland Scottish parliament region in 2021.

And Galloway is certainly not an unproblematic figure in the workers’ movement: not least for his position on Scottish independence, his failure to turn the positive aspects of the support he has amongst workers and youth from an Asian Muslim background into a bridge towards other sections of the working class – he left behind little in Bethnal Green or Bradford – and what can only be described, mildly, as his divisive social conservatism on issues such as trans rights that will not unite the working class around a shared programme.

TUSC faced a not dissimilar situation when considering the participation of the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) in 2010, with Bob Crow and the Socialist Party critical of their position on the 2009 Lindsey oil refinery workers’ strike and the RMT-initiated No2EU European election challenge of the same year.

But TUSC was established as a federal ‘umbrella’ coalition, with core policies for different elections only agreed, after debate, by consensus. Participating candidates and organisations are accountable only for their own campaigns – a ‘united front’ marching separately but striking together under the same banner at the ballot box.

And so it was felt that the drawbacks of the SWP’s involvement could be overcome, as it proved. They only withdrew from TUSC in 2017 because they decided they would no longer stand in elections and have been invited to rejoin in the new circumstances of Starmer’s leadership.

The Socialist Party takes the same approach to the Workers Party as any other political trend in the workers’ movement and, while continuing to raise our criticisms of them, will support the proposal for observer status.