The editorial of Socialism Today, 3 May 2022, no.257

Some events become iconic when they are subsequently seen as a representative summation of a new turning point in social, economic or political developments. The fall of the Berlin Wall is one example. It symbolises the collapse of Stalinism in Russia and Eastern Europe and the end of the Cold War framing of world power relations as that between competing social systems: capitalism in the West, and the non-capitalist Stalinist states of the East.

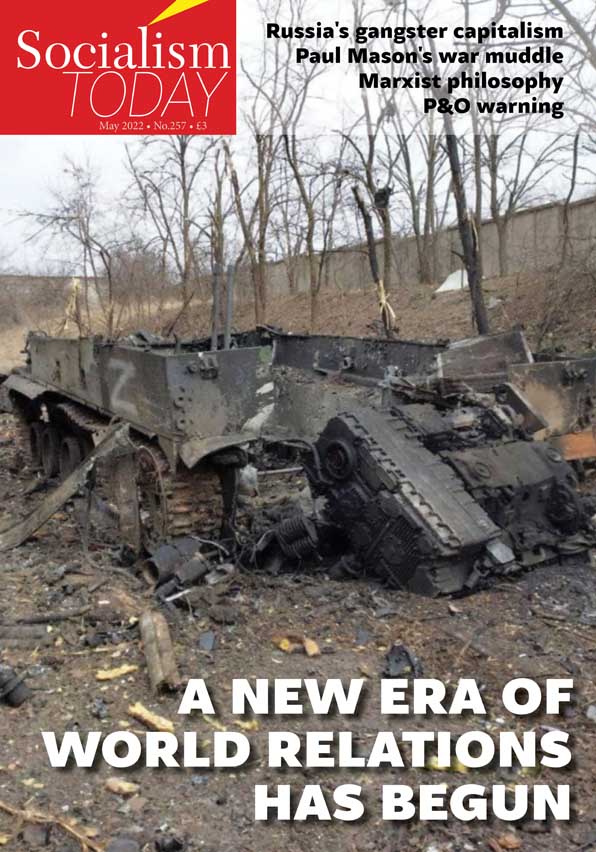

The rotting of the Stalinist regimes under the internal contradictions of totalitarian rule – the mirror opposite of workers’ democracy – had been an extended process as the bureaucracy moved from being a relative to an absolute fetter on the economy and society. But that did not diminish the significance of the November 1989 drama. And while it too is the product of underlying and ongoing processes, the Russian invasion of Ukraine on February 24 will also come to be seen as another pivotal moment in history.

Already the war, however it finishes, has upset the global architecture of treaty organisations, diplomatic conventions and so on built up over the past 30 years. This international machinery was either remoulded from institutions of the Cold War era (GATT became the World Trade Organisation, for example) or superseded them (the G7 and G20, the International Criminal Court, the COP climate summits). Together they constituted the means by which the conflicting interests of the world’s most powerful capitalist nation states (and the formally ‘non-market economy’ Chinese regime) were mediated in the post-Stalinist world.

This liberal international ‘rules-based system’ underpinned the hegemony of US imperialism into the new millennium. It opened up world markets to unrestrained access for US capital in particular, under the banner of ‘globalisation’. The part in the new global alignment of the now capitalist Russian Federation, the international legal successor to the USSR, was that of a ‘petro-power’. It became a significant commodity producer within the world economy particularly of hydrocarbons and food and agricultural products, but not then a disrupter of the US-shaped order.

Even then, however, the USA’s moment as an unchallenged hyperpower was brief, historically speaking. It was progressively broken down by 9/11, the imperial overreach of the Iraq war, and the financial crisis of 2007-08 – and in turn replaced by an increasingly multi-polar world. The US was still the foremost economic and military power but in a now contested world.

This included the newly-established Russian capitalist class. As it consolidated its position it moved from its initial obsequiousness to US imperialism in the first period of the restoration of capitalism to an assertion of its own imperialist interests, not least in Russia’s ‘near-abroad’ of Georgia, Transdniestria in Moldova, Armenia and Azerbaijan – and Ukraine.

Now, in an era without a global hegemon, and with a major world power attempting to settle underlying conflicts not by diplomacy but by force of arms, a new phase opens up, internationally and in Britain too.

The tasks for the Marxist press at this turning point must be both to analyse the processes and class interests involved and to work towards a programme that can help prepare the working class and its organisations for the challenges ahead.

A catastrophic reversal

Stalinism was not an example of genuine socialism, which means the democratic control of society by the working class not the dictatorship of a privileged bureaucracy. But the planned economy of the Stalinist states – with private ownership of the dominant sectors of industry and the imperatives of market relations curbed – saw enormous economic progress made for a whole historical period even under the rule of the bureaucracy.

There are many different figures to illustrate this but even the ideologically pro-capitalist Economist magazine, on the hundredth anniversary of the 1917 Russian revolution, had to acknowledge that while “the rest of the world wallowed in the Depression” of the inter-war years, manufacturing output in the USSR grew by over 170% from 1928 to 1940 (11 November 2017). They also conceded that, at the apogee of Russian Stalinism’s economic development in relation to the capitalist world in the 1960s, “when the USSR premier Nikita Khrushchev told the West ‘we will bury you’ the threat seemed credible” (15 December 2018).

The collapse when it came was of catastrophic proportions. There was arguably a greater reversal of economic fortunes even than that experienced by Germany in the aftermath of the first world war, which saw the world’s third largest economy in 1914 lose its colonies and bear the onerous terms of the Versailles treaty.

From 1991 to 1994 Russian male life expectancy dropped by five years, as mass privatisation ‘shock therapy’ was unleashed. Russia from the 1990s moved from being at the centre of the world’s second largest economy – the USSR was such even as late as 1985, by which point the sclerotic bureaucracy was increasingly unable to develop a modern advanced economy – to its current (pre-Ukraine invasion) position of twelfth. From an economy half the size of the US to one-thirteenth the size (2019 IMF rankings). But still weighed down with the world’s third or fourth largest military budget, and nuclear weapons spending ($8.5 billion in 2019) still one-quarter of that of the USA ($35.4bn).

The Russian capitalism that has developed since from the ruins of Stalinism really is an armed petro-state resting on chicken legs. But it is still a capitalist state defending capitalist interests, not those of the working class or the national rights of the peoples of the region.

Gangster capitalism

In his review in this edition of Socialism Today [May 2022] of Putin’s People, a recent book charting the rise of the brutal regime of Russian president Vladimir Putin, Peter Taaffe explains how the collapse of the planned economy precipitated the formation of a new capitalist class out of former bureaucrats, top managers, traders, financiers, organised crime groups – and sections of the former Stalinist secret police, the KGB, with the ex-minor operative Putin “completely at home” as he climbed his way to power in “this violent murky world”.

The overwhelming interest of this new capitalist class in formation was self-enrichment. They were, and still are, rent-grabbers, in particular from the four trillion dollars of oil and gas exports that have flowed from Russia in the past two decades alone.

But under capitalism a new source of value inevitably also becomes a new source of competition to control it – both between individual capitalist companies, and between nationally-organised capitalist classes.

US imperialism, and German capitalism too through its dominant position within the European Union (EU), sought their share. ‘Londongrad’, under both New Labour and the Tories, played its role by aiding the oligarchs to launder their loot.

Meanwhile the similarly emergent new elites in the ex-Stalinist states of Eastern Europe and the former countries of the USSR – mini-me gangster capitalists all – either gravitated to the US and the EU (and within the EU or the US-dominated NATO alliance generally sought the hardest measures against their Russian counterparts) or remained with varying degrees of acquiescence within Russia’s ‘sphere of influence’.

To assert their imperial interests in this situation, but also to counter centrifugal forces within the Russian Federation from the Urals, Siberia, Tatarstan, the North Caucasus and elsewhere, the consolidating Russian state moved to strengthen its apparatus. It developed an appropriate ‘Greater Russia’ ideology to attempt to legitimise its rule. And it looked for opportunities to unfreeze the world order established after the collapse of Stalinism.

These are the fundamental broad underlying causes of the 24 February invasion and the terrible suffering being meted out on the peoples of Ukraine today. They are further explored by Tony Saunois in his article in this edition [the May 2022 issue of Socialism Today], responding to the confused arguments made by the radical journalist Paul Mason about which side in the war is ‘progressive’.

It is necessary to clear a way through the fog of war. The economic consequences alone of the Ukraine crisis, on top of the effects of the pandemic, will usher in a new, harsher battle between the classes including in Britain, as Hannah Sell’s article explains [in the May 2022 issue of Socialism Today].

A new era of world relations has begun. Notwithstanding the great disparity between the two, the conflict between the Russian state and US imperialism and its NATO instrument is a clash between rival imperialisms, with no ‘side’ offering anything to the working class. The task of building the forces of world socialism has become ever more urgent.